Bruker:Cocu/Kladd: Forskjell mellom sideversjoner

... |

... |

||

| Linje 79: | Linje 79: | ||

== Mulighet for ekstraterrestrisk liv == |

== Mulighet for ekstraterrestrisk liv == |

||

| ⚫ | <noinclude>[[Image:Blacksmoker in Atlantic Ocean.jpg|thumb|A [[black smoker]] in the Atlantic Ocean. Driven by geothermal energy, this and [[Lost City (hydrothermal field)|other types]] of hydrothermal vents create [[Chemical equilibrium|chemical disequilibria]] that can provide energy sources for life.]] |

||

<noinclude><!-- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Europa has emerged as one of the top Solar System locations in terms of [[Planetary habitability|potential habitability]] and possibly, hosting [[extraterrestrial life]].<ref name="Schulze-Makuch2001">{{cite web |title=Alternative Energy Sources Could Support Life on Europa |url=http://www.geo.utep.edu/pub/dirksm/geobiowater/pdf/EOS27March2001.pdf |author=Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; and Irwin, Louis N. |work=Departments of Geological and Biological Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso |year=2001 |accessdate=2007-12-21 |format=PDF | archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20060703033956/http://www.geo.utep.edu/pub/dirksm/geobiowater/pdf/EOS27March2001.pdf| archivedate = July 3, 2006}}</ref> Life could exist in its under-ice ocean, perhaps subsisting in an environment similar to Earth's deep-ocean [[hydrothermal vent]]s or the Antarctic [[Lake Vostok]].<ref name="NASA1999">[http://science.nasa.gov/newhome/headlines/ast10dec99_2.htm ''Exotic Microbes Discovered near Lake Vostok''], Science@NASA (December 10, 1999)</ref> Life in such an ocean could possibly be similar to [[Microorganism|microbial]] life on Earth in the [[deep ocean]].<ref name="EuropaLife"/><ref name="Jones2001">Jones, Nicola; [http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn1647 ''Bacterial explanation for Europa's rosy glow''], NewScientist.com (11 December 2001)</ref> So far, there is no evidence that life exists on Europa, but the likely presence of liquid water has spurred calls to send a probe there.<ref name="Phillips2006">Phillips, Cynthia; [http://www.space.com/searchforlife/seti_europa_060928.html ''Time for Europa''], Space.com (28 September 2006)</ref> |

Europa has emerged as one of the top Solar System locations in terms of [[Planetary habitability|potential habitability]] and possibly, hosting [[extraterrestrial life]].<ref name="Schulze-Makuch2001">{{cite web |title=Alternative Energy Sources Could Support Life on Europa |url=http://www.geo.utep.edu/pub/dirksm/geobiowater/pdf/EOS27March2001.pdf |author=Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; and Irwin, Louis N. |work=Departments of Geological and Biological Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso |year=2001 |accessdate=2007-12-21 |format=PDF | archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20060703033956/http://www.geo.utep.edu/pub/dirksm/geobiowater/pdf/EOS27March2001.pdf| archivedate = July 3, 2006}}</ref> Life could exist in its under-ice ocean, perhaps subsisting in an environment similar to Earth's deep-ocean [[hydrothermal vent]]s or the Antarctic [[Lake Vostok]].<ref name="NASA1999">[http://science.nasa.gov/newhome/headlines/ast10dec99_2.htm ''Exotic Microbes Discovered near Lake Vostok''], Science@NASA (December 10, 1999)</ref> Life in such an ocean could possibly be similar to [[Microorganism|microbial]] life on Earth in the [[deep ocean]].<ref name="EuropaLife"/><ref name="Jones2001">Jones, Nicola; [http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn1647 ''Bacterial explanation for Europa's rosy glow''], NewScientist.com (11 December 2001)</ref> So far, there is no evidence that life exists on Europa, but the likely presence of liquid water has spurred calls to send a probe there.<ref name="Phillips2006">Phillips, Cynthia; [http://www.space.com/searchforlife/seti_europa_060928.html ''Time for Europa''], Space.com (28 September 2006)</ref> |

||

| Linje 94: | Linje 93: | ||

{{quote|We’ve spent quite a bit of time and effort trying to understand if Mars was once a habitable environment. Europa today, probably, is a habitable environment. We need to confirm this … but Europa, potentially, has all the ingredients for life … and not just four billion years ago … but today.<ref name="Europabudget"/>}} |

{{quote|We’ve spent quite a bit of time and effort trying to understand if Mars was once a habitable environment. Europa today, probably, is a habitable environment. We need to confirm this … but Europa, potentially, has all the ingredients for life … and not just four billion years ago … but today.<ref name="Europabudget"/>}} |

||

In November 2011, a team of researchers presented evidence in the journal ''Nature'' suggesting the existence of vast lakes of liquid water entirely encased in the moon's icy outer shell and distinct from a liquid ocean thought to exist farther down beneath the ice shell.<ref name="europagreatlake"/><ref name="europagreatlakeairhart"/> If confirmed, the lakes could be yet another potential habitat for life. |

In November 2011, a team of researchers presented evidence in the journal ''Nature'' suggesting the existence of vast lakes of liquid water entirely encased in the moon's icy outer shell and distinct from a liquid ocean thought to exist farther down beneath the ice shell.<ref name="europagreatlake"/><ref name="europagreatlakeairhart"/> If confirmed, the lakes could be yet another potential habitat for life.</noinclude> |

||

== Utforskning == |

== Utforskning == |

||

Sideversjonen fra 14. feb. 2012 kl. 22:40

| Europa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Europa i tilnærmet naturlige farger. Det fremtredende krateret nede til høyre er Pwyll og de mørkere partiene er områder der hoveddelen av Europas vannholdige is har et høyere innhold av mineraler. | |||||||||||

| Oppdagelse | |||||||||||

| Oppdaget av | Galileo Galilei Simon Marius | ||||||||||

| Oppdaget | 8. januar 1610 | ||||||||||

| Alternative navn | Jupiter II | ||||||||||

| Baneparametre[1] Epoke 8. januar 2004 | |||||||||||

| Periapsis | 664 862 km[a] | ||||||||||

| Apoapsis | 676 938 km | ||||||||||

| Gjennomsnittlig baneradius | 670 900 km 0,00448 AE[2] | ||||||||||

| Eksentrisitet | 0,009[2] | ||||||||||

| Omløpstid | 3,551181 jorddøgn[2] | ||||||||||

| Gjennomsnittsfart | 13,74 km/s[2] | ||||||||||

| Inklinasjon | 0,47°[b][2] | ||||||||||

| Moderplanet | Jupiter | ||||||||||

| Fysiske egenskaper | |||||||||||

| Gjennomsnittlig radius | 1 569 km[2] | ||||||||||

| Overflatens areal | 30 900 000 km²[c] | ||||||||||

| Volum | 15 930 000 000 km³[c] | ||||||||||

| Masse | 48 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 kg[2] | ||||||||||

| Middeltetthet | 3,01 g/cm³[2] | ||||||||||

| Gravitasjon ved ekvator | 1,314 m/s² 0,134 g[a] | ||||||||||

| Unnslipningshastighet | 2,025 km/s | ||||||||||

| Rotasjon | Bundet | ||||||||||

| Aksehelning | 0,1°[S 1] | ||||||||||

| Overflaterefleksjon | 0,67 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Tilsynelatende størrelsesklasse | 5,29[d][3] | ||||||||||

| Atmosfæriske egenskaper | |||||||||||

| Atmosfærisk trykk | 0.1 pascal[S 3] | ||||||||||

Europa (gresk: Ευρώπη) eller Jupiter II er den sjette nærmeste månen til planeten Jupiter og den minste av de fire galileiske måner, men likevel en av de største legemene i solsystemet. Europa ble oppdaget av Galileo Galilei i 1610[4] og muligens uavhengig av Simon Marius rundt samme tid. Gradvise mer i-dybden-observasjoner av Europa foregått gjennom århundrer ved bruk av bakkebaserte teleskoper og ved forbiflyvninger med romsonder fra og med 1970-tallet.

Europa er noe mindre enn månen og består primært av silikate bergarter, sannsynligvis en kjerne av jern og den har en tynn atmosfære hovedsakelig sammensatt av oksygen. Overflaten, som i stort sett består av is, er en av de jevneste i solsystemet og er tverrstripet av sprekker og riller og med relativt få kratre. Den tilsynelatende unge glattheten til overflaten har ført til teorier om at et underjordisk hav av vann som kan tenkes å fungere som opphodssted for utenomjordisk liv kan eksistere.[5] Denne hypotesen foreslår at varmeenergi fra tidevannsbøyning gjør at havene forblir flytende og driver geologisk aktivitet på samme måte som platetektonikk[6]

Selv om det kun er forbiflyvningsoppdrag som har besøkt månen har Europas spennende egenskaper ført til flere ambisiøse forslag om utforskninger av månen. Galileo-oppdraget som startet i 1989 har gitt hovedmengden av de nåværende data om Europa. Et nytt oppdrag til Jupiters ismåner, Europa Jupiter System Mission (EJSM) ble foreslått med oppskytning i 2020.[7] Antydningen om utenomjordisk liv har sikret månen en høy profil og har ført til en jevn lobbyvirksomhet for fremtidige oppdrag.[8][9]

Europa ble oppdaget av Galileo Galilei i januar 1610,[4] og muligvis uavhengig av Simon Marius rundt samme tid. Månener oppkalt etter en føniksk adelskvinne i gresk mytologi, Europa, som ble kurtisert av Zevs og ble dronning av Kreta.

Sammen med Jupiters tre andre største måner, Io, Ganymedes og Callisto ble Europa oppdaget av Galileo Galilei. Den første rapporterte observasjonen av Io ble gjort av Galileo 7. januar 1610 og den ble oppdaget ved bruk av et 20x refrakorteleskop ved Universitetet i Padova. Under den observasjonen kunne imidlertid ikke Galileo skille Io og Europa på grunn av den lave kraften i teleskopet, så de to ble registrert som ett enkelt lyspunkt. Io og Europa ble først observert som to separate punkter da Galilei observerte det jovianske systemet den påfølgende dagen, 8. januar 1610. Denne datoen er også brukt som observasjonsdato for Europa av IAU.[4]

Som alle de andre galileiske månene er Europa oppkalt etter en av Zevs' elskerinner, det greske motstykket til Jupiter, i dette tilfellet Europa, datter av kongen av Tyr. Navnesystemet ble foreslått av Simon Marius, som tilsynelatende oppdaget satellittene uavhengig, selv om Galileo hevdet at Marius hadde plagiert ham. Marius tilskrev forslaget til Johannes Kepler.[10][11]

Nanvnene ble tatt ut av bruk over en betydelig periode og ble ikke tatt tilbake i generell bruk før på midten av det 20. århundre.[L 1] I mye tidligere astronomisk litteratur ble Europa bare referert til ved sine romertall, betegnet som Jupiter II (et system introdusert av Galileo) eller som «Jupiters andre måne». I 1892 førte oppdagelsen av Amalthea, som har bane nærmere Jupiter, at Eurapa ble forskjøvet til tredje posisjon. Voyager-sonden oppdaget ytterligere tre indre måner i 1979, så Europa er nå betraktet som Jupiters sjette satellitt, selv om den fremdeles refereres til som Jupiter II.[L 1]

Omløp og rotasjon

Europa går en runde rundt Jupiter på litt over tre og en halv dag med en baneradius på 670 900 km. Med en eksentrisitet på kun 0,009 er selve banen nesten sirkulær og inklinasjonen relativt til det jovianske ekvatorplanet er liten, kun 0,470°.[12] Som de andre galileiske månene har Europa en bundet rotasjon med Jupiter der den ene halvkulen alltid vender mot planeten. På grunn av dette er der et sub-joviansk punkt på Europas overflate hvor Jupiter tilsynelatende henger direkte over. Europas nullmeridian er linjen som krysser dette punktet.[13] Forskning antyder ay tidevannslåsingen ikke er fullstendig, siden en ikke-synkron rotatsjon har blitt foreslått: Europa roterer raskere enn den går i bane rundt Jupiter, eller den gjorde i det minste det i fortiden. Dette antyder en asymmetri i fordelingen av den indre massen og at et underjordisk lag av væske separerer isskorpen fra bergartene i det indre.[L 2]

Den lille eksentrisiteten i Europas bane som opprettholdes av den gravitasjonelle forstyrrelsen fra de andre galileiske månene forårsaker at Europas sub-jovianske punkt pendler rundt en gjennomsnittlig posisjon. Når Europa kommer litt nærmere Jupiter, øker den gravitasjonelle påvirkningen og forårsaker at månen strekker seg mot den. Når Europa beveger seg noe vekk fra Jupiter avtar planetens gravitasjonskraft og forårsaker at månen går tilbake til en mer sfærisk form. Baneeksentrisiteten til Europa heves kontiunerlig av den gjennomsnittlige bevegelsesresonansen med Io.[L 3] Dermed forårsaker tidevannsfleksingen at Europas indre blir en varmekilde som muligens gjør at et hav kan forbli flytende og drive geologiske prosesser under overflaten.[6][L 3]The ultimate source of this energy is Jupiter's rotation, which is tapped by Io through the tides it raises on Jupiter and is transferred to Europa and Ganymede by the orbital resonance.[L 3][14][14]

Fysiske egenskaper

Europa er så vidt mindre enn jordens måne. Med en diameter like over 3 100 km er den det sjette største månen og det femtende største objektet i solsystemet. Selv om månen er den klart minste av de galileiske månene er den likevel mer massiv enn alle kjente måner i solsystemet som er mindre enn den til sammen.[N 1] Tettheten antyder at den er tilsvarende de terrestriske planetene i sammensetning, primært bestående av silikate bergarter.[L 4]

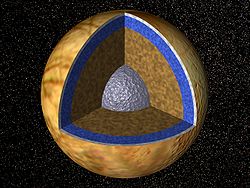

Indre struktur

Det antas at Europa har et ytre lag av vann med en tykkelse på ca. 100 km; noe som en øvre skorpe av frossen is og noe som et flytende hav under isen. Nyere data om magnetfeltet fra Galileo-sonden viste at Europa har et fremkalt magnetfelt gjennom vekselvirkning med Jupiters magnetfelt, noe som antyder tilstedeværelsen av et konduktivt underjordisk lag. Dette laget er sannsynligvis et flytende saltvannshav. Skorpen antas å ha gjennomgått en forskyvning på 80°, noe som ville vært usannsynlig hvis isen satt fast i mantelen.[15] Europa har sannsynligvis en metallisk jernkjerne.[L 5]

Overflateformasjoner

Europa er et av de jevneste objektene i solsystemet.[16] De dominerende markeringene på kryss og tvers av månen ser ut til å være hovedsakelig albedoformasjoner, som understreker en lav topografi. På grunn av at overflaten er tektonisk aktiv og ung finnes det også få nedslagskratere på Europa.[17][18] Europas isete overflate gir den en albedo (lysreflektivitet) på 0,64, en av de høyeste av alle månene.[12][18] Dette synes å indikere en ung og aktiv overflate; basert på estimert frekvens av kometbombardementer som Europa sannsynligvis gjennomgår er overflaten 20–180 millioner år gammel.[L 6] Det er foreløpig ingen full vitenskapelig enighet om de noen ganger motstridende forklaringene på Europas overflateformasjoner.[19]

Strålingsnivået på Europas overflate er tilsvarende en dose på ca. 540 rem (5 400 mSv) per dag,[20] en strålingsmengde som ville forårsaket sykdom eller død for mennesker.[L 7]Lineae

Europa's most striking surface features are a series of dark streaks crisscrossing the entire globe, called lineae (engelsk: lines). Close examination shows that the edges of Europa's crust on either side of the cracks have moved relative to each other. The larger bands are more than 20 km (12 mi) across, often with dark, diffuse outer edges, regular striations, and a central band of lighter material.[21] The most likely hypothesis states that these lineae may have been produced by a series of eruptions of warm ice as the Europan crust spread open to expose warmer layers beneath.[22] The effect would have been similar to that seen in the Earth's oceanic ridges. These various fractures are thought to have been caused in large part by the tidal stresses exerted by Jupiter. Since Europa is tidally locked to Jupiter, and therefore always maintains the same approximate orientation towards the planet, the stress patterns should form a distinctive and predictable pattern. However, only the youngest of Europa's fractures conform to the predicted pattern; other fractures appear to occur at increasingly different orientations the older they are. This could be explained if Europa's surface rotates slightly faster than its interior, an effect which is possible due to the subsurface ocean mechanically decoupling the moon's surface from its rocky mantle and the effects of Jupiter's gravity tugging on the moon's outer ice crust.[23] Comparisons of Voyager and Galileo spacecraft photos serve to put an upper limit on this hypothetical slippage. The full revolution of the outer rigid shell relative to the interior of Europa occurs over a minimum of 12,000 years.[24]

Andre geologiske formasjoner

Other features present on Europa are circular and elliptical lenticulae (Latin for "freckles"). Many are domes, some are pits and some are smooth, dark spots. Others have a jumbled or rough texture. The dome tops look like pieces of the older plains around them, suggesting that the domes formed when the plains were pushed up from below.[25]

One hypothesis states that these lenticulae were formed by diapirs of warm ice rising up through the colder ice of the outer crust, much like magma chambers in the Earth's crust.[25] The smooth, dark spots could be formed by meltwater released when the warm ice breaks through the surface. The rough, jumbled lenticulae (called regions of "chaos"; for example, Conamara Chaos) would then be formed from many small fragments of crust embedded in hummocky, dark material, appearing like icebergs in a frozen sea.[26]

An alternative hypothesis suggest that lenticulae are actually small areas of chaos and that the claimed pits, spots and domes are artefacts resulting from over-interpretation of early, low-resolution Galileo images. The implication is that the ice is too thin to support the convective diapir model of feature formation. [27] [28]

In November 2011, a team of researchers from the University of Texas at Austin and elsewhere presented evidence in the journal Nature suggesting that many "chaos terrain" features on Europa sit atop vast lakes of liquid water.[29][30] These lakes would be entirely encased in the moon's icy outer shell and distinct from a liquid ocean thought to exist farther down beneath the ice shell. Full confirmation of the lakes' existence will require a space mission designed to probe the ice shell either physically or indirectly, for example using radar.

Underjordiske hav

Most planetary scientists believe that a layer of liquid water exists beneath Europa's surface, kept warm by tidally generated heat.[31] The heating by radioactive decay, which is almost the same as in Earth (per kg of rock), cannot provide necessary heating in Europa because the volume-to-surface ratio is much lower due to the moon's smaller size. Europa's surface temperature averages about 110 K (−160 °C; −260 °F) at the equator and only 50 K (−220 °C; −370 °F) at the poles, keeping Europa's icy crust as hard as granite.[32] The first hints of a subsurface ocean came from theoretical considerations of tidal heating (a consequence of Europa's slightly eccentric orbit and orbital resonance with the other Galilean moons). Galileo imaging team members argue for the existence of a subsurface ocean from analysis of Voyager and Galileo images.[31] The most dramatic example is "chaos terrain", a common feature on Europa's surface that some interpret as a region where the subsurface ocean has melted through the icy crust. This interpretation is extremely controversial. Most geologists who have studied Europa favor what is commonly called the "thick ice" model, in which the ocean has rarely, if ever, directly interacted with the present surface.[33] The different models for the estimation of the ice shell thickness give values between a few kilometers and tens of kilometers.[34]

The best evidence for the thick-ice model is a study of Europa's large craters. The largest impact structures are surrounded by concentric rings and appear to be filled with relatively flat, fresh ice; based on this and on the calculated amount of heat generated by Europan tides, it is predicted that the outer crust of solid ice is approximately 10–30 km (6–19 mi) thick, including a ductile "warm ice" layer, which could mean that the liquid ocean underneath may be about 100 km (60 mi) deep.[35] This leads to a volume of Europa's oceans of 3 × 1018 m3, slightly more than two times the volume of Earth's oceans.

The thin-ice model suggests that Europa's ice shell may be only a few kilometers thick. However, most planetary scientists conclude that this model considers only those topmost layers of Europa's crust which behave elastically when affected by Jupiter's tides. One example is flexure analysis, in which the moon's crust is modeled as a plane or sphere weighted and flexed by a heavy load. Models such as this suggest the outer elastic portion of the ice crust could be as thin as 200 meter (660 ft). If the ice shell of Europa is really only a few kilometers thick, this "thin ice" model would mean that regular contact of the liquid interior with the surface could occur through open ridges, causing the formation of areas of chaotic terrain.[34]

In late 2008, it was suggested Jupiter may keep Europa's oceans warm by generating large planetary tidal waves on the moon because of its small but non-zero obliquity. This previously unconsidered kind of tidal force generates so-called Rossby waves that travel quite slowly, at just a few kilometers per day, but can generate significant kinetic energy. For the current axial tilt estimate of 0.1 degree, the resonance from Rossby waves would store 7.3×1017 J of kinetic energy, which is two hundred times larger than that of the flow excited by the dominant tidal forces.[36][37] Dissipation of this energy could be the principal heat source of Europa's ocean.

The Galileo orbiter found that Europa has a weak magnetic moment, which is induced by the varying part of the Jovian magnetic field. The field strength at the magnetic equator (about 120 nT) created by this magnetic moment is about one-sixth the strength of Ganymede's field and six times the value of Callisto's.[38] The existence of the induced moment requires a layer of a highly electrically conductive material in the moon's interior. The most plausible candidate for this role is a large subsurface ocean of liquid saltwater.[39] Spectrographic evidence suggests that the dark, reddish streaks and features on Europa's surface may be rich in salts such as magnesium sulfate, deposited by evaporating water that emerged from within.[40] Sulfuric acid hydrate is another possible explanation for the contaminant observed spectroscopically.[41] In either case, since these materials are colorless or white when pure, some other material must also be present to account for the reddish color, and sulfur compounds are suspected.[42]

Atmosfære

Observations with the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph of the Hubble Space Telescope, first described in 1995, revealed that Europa has a tenuous atmosphere composed mostly of molecular oxygen (O2).[43][44] The surface pressure of Europa's atmosphere is 0.1 μPa, or 10−12 times that of the Earth.[45] In 1997, the Galileo spacecraft confirmed the presence of a tenuous ionosphere (an upper-atmospheric layer of charged particles) around Europa created by solar radiation and energetic particles from Jupiter's magnetosphere,[46][47] providing evidence of an atmosphere.

Unlike the oxygen in Earth's atmosphere, Europa's is not of biological origin. The surface-bounded atmosphere forms through radiolysis, the dissociation of molecules through radiation.[48] Solar ultraviolet radiation and charged particles (ions and electrons) from the Jovian magnetospheric environment collide with Europa's icy surface, splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen constituents. These chemical components are then adsorbed and "sputtered" into the atmosphere. The same radiation also creates collisional ejections of these products from the surface, and the balance of these two processes forms an atmosphere.[49] Molecular oxygen is the densest component of the atmosphere because it has a long lifetime; after returning to the surface, it does not stick (freeze) like a water or hydrogen peroxide molecule but rather desorbs from the surface and starts another ballistic arc. Molecular hydrogen never reaches the surface, as it is light enough to escape Europa's surface gravity.[50][51]

Observations of the surface have revealed that some of the molecular oxygen produced by radiolysis is not ejected from the surface. Because the surface may interact with the subsurface ocean (considering the geological discussion above), this molecular oxygen may make its way to the ocean, where it could aid in biological processes.[52] One estimate suggests that, given the turnover rate inferred from the apparent ~0.5 Gyr maximum age of Europa's surface ice, subduction of radiolytically generated oxidizing species might well lead to oceanic free oxygen concentrations that are comparable to those in terrestrial deep oceans.[53]

The molecular hydrogen that escapes Europa's gravity, along with atomic and molecular oxygen, forms a torus (ring) of gas in the vicinity of Europa's orbit around Jupiter. This "neutral cloud" has been detected by both the Cassini and Galileo spacecraft, and has a greater content (number of atoms and molecules) than the neutral cloud surrounding Jupiter's inner moon Io. Models predict that almost every atom or molecule in Europa's torus is eventually ionized, thus providing a source to Jupiter's magnetospheric plasma. [54]

Mulighet for ekstraterrestrisk liv

Europa has emerged as one of the top Solar System locations in terms of potential habitability and possibly, hosting extraterrestrial life.[55] Life could exist in its under-ice ocean, perhaps subsisting in an environment similar to Earth's deep-ocean hydrothermal vents or the Antarctic Lake Vostok.[56] Life in such an ocean could possibly be similar to microbial life on Earth in the deep ocean.[57][58] So far, there is no evidence that life exists on Europa, but the likely presence of liquid water has spurred calls to send a probe there.[59]

Until the 1970s, life, at least as the concept is generally understood, was believed to be entirely dependent on energy from the Sun. Plants on Earth's surface capture energy from sunlight to photosynthesize sugars from carbon dioxide and water, releasing oxygen in the process, and are then eaten by oxygen-respiring animals, passing their energy up the food chain. Even life in the deep ocean, far below the reach of sunlight, was believed to obtain its nourishment either from the organic detritus raining down from the surface, or by eating animals that in turn depend on that stream of nutrients.[60] An environment's ability to support life was thus thought to depend on its access to sunlight.

However, in 1977, during an exploratory dive to the Galapagos Rift in the deep-sea exploration submersible Alvin, scientists discovered colonies of giant tube worms, clams, crustaceans, mussels, and other assorted creatures clustered around undersea volcanic features known as black smokers.[60] These creatures thrive despite having no access to sunlight, and it was soon discovered that they comprise an entirely independent food chain. Instead of plants, the basis for this food chain was a form of bacterium that derived its energy from oxidization of reactive chemicals, such as hydrogen or hydrogen sulfide, that bubbled up from the Earth's interior. This chemosynthesis revolutionized the study of biology by revealing that life need not be sun-dependent; it only requires water and an energy gradient in order to exist. It opened up a new avenue in astrobiology by massively expanding the number of possible extraterrestrial habitats.

While the tube worms and other multicellular eukaryotic organisms around these hydrothermal vents respire oxygen and thus are indirectly dependent on photosynthesis, anaerobic chemosynthetic bacteria and archaea that inhabit these ecosystems provide a possible model for life in Europa's ocean.[53] The energy provided by tidal flexing drives active geological processes within Europa's interior, just as they do to a far more obvious degree on its sister moon Io. While Europa, like the Earth, may possess an internal energy source from radioactive decay, the energy generated by tidal flexing would be several orders of magnitude greater than any radiological source.[61] However, such an energy source could never support an ecosystem as large and diverse as the photosynthesis-based ecosystem on Earth's surface.[62] Life on Europa could exist clustered around hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, or below the ocean floor, where endoliths are known to inhabit on Earth. Alternatively, it could exist clinging to the lower surface of the moon's ice layer, much like algae and bacteria in Earth's polar regions, or float freely in Europa's ocean.[63] However, if Europa's ocean were too cold, biological processes similar to those known on Earth could not take place. Similarly, if it were too salty, only extreme halophiles could survive in its environment.[63] In September 2009, planetary scientist Richard Greenberg calculated that cosmic rays impacting on Europa's surface convert some water ice into free oxygen (O2) which could then be absorbed into the ocean below as water wells up to fill cracks. Via this process, Greenberg estimates that Europa's ocean could eventually achieve an oxygen concentration greater than that of Earth's oceans within just a few million years. This would enable Europa to support not merely anaerobic microbial life but potentially larger, aerobic organisms such as fish.[64]

In 2006, Robert T. Pappalardo, an assistant professor in the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado in Boulder said,

We’ve spent quite a bit of time and effort trying to understand if Mars was once a habitable environment. Europa today, probably, is a habitable environment. We need to confirm this … but Europa, potentially, has all the ingredients for life … and not just four billion years ago … but today.[9]

In November 2011, a team of researchers presented evidence in the journal Nature suggesting the existence of vast lakes of liquid water entirely encased in the moon's icy outer shell and distinct from a liquid ocean thought to exist farther down beneath the ice shell.[29][30] If confirmed, the lakes could be yet another potential habitat for life.

Utforskning

Fremtidige oppdrag

Foreslåtte og avbrutte romsonder

Noter og referanser

- Noter

- Litteraturhenvisninger

- ^ a b Marazzini (2005), s. 391–407

- ^ Geissler (1998), s. 368–70

- ^ a b c Showman (1997), s. 93–111

- ^ Jeffrey (2000), s. 226–265

- ^ Kivelson (2000), s. 1 340–1 343

- ^ Schenk (2004), kap. 18

- ^ Glasstone (1962), s. 592–593

- Netthenvisninger

- ^ «JPL HORIZONS solar system data and ephemeris computation service». Solar System Dynamics (engelsk). NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Besøkt 22. januar 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Overview of Europa Facts». NASA (engelsk). Besøkt 22. januar 2012.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald K. (13. juli 2006). «Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters» (engelsk). JPL Solar System Dynamics. Besøkt 22. januar 2012.

- ^ a b c Blue, Jennifer (9. november 2009). «Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers» (engelsk). USGS. Besøkt 12. februar 2012.

- ^ Tritt, Charles S. (2002). «Possibility of Life on Europa» (engelsk). Milwaukee School of Engineering. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ a b «Tidal Heating». geology.asu.edu (engelsk). Arkivert fra originalen 29. mars 2006. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ «NASA and ESA Prioritize Outer Planet Missions» (engelsk). NASA. 2009. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ Friedman, Louis (14. desember 2005). «Projects: Europa Mission Campaign; Campaign Update: 2007 Budget Proposal» (engelsk). The Planetary Society. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ a b David, Leonard (7. februar 2006). «Europa Mission: Lost In NASA Budget» (engelsk). Space.com. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ «Simon Marius». Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (engelsk). University of Arizona. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ Marius, S.; (1614) Mundus Iovialis anno M.DC.IX Detectus Ope Perspicilli Belgici [1], hvor han tilskriver forslaget til Johannes Kepler

- ^ a b «Europa, a Continuing Story of Discovery». Project Galileo (engelsk). NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ «Planetographic Coordinates» (engelsk). Wolfram Research. 2010. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ a b «Tidal heating of Io and orbital evolution of the Jovian satellites». 1982.

- ^ Cowen, Ron. «A Shifty Moon». Science News (engelsk). Besøkt 14. februar 2012.

- ^ «Europa: Another Water World?». Project Galileo: Moons and Rings of Jupiter (engelsk). NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2001. Besøkt 14. februar 2012.

- ^ Arnett, Bill (7. november 1996). «Europa» (engelsk). Besøkt 14. februar 2012.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Calvin J. «Jupiter's Moon Europa» (engelsk). Besøkt 14. februar 2012.

- ^ «High Tide on Europa». Astrobiology Magazine (engelsk). astrobio.net. 2007. Besøkt 14. februar 2012.

- ^ Ringwald, Frederick A. (29. februar 2000). «SPS 1020 (Introduction to Space Sciences)» (engelsk). California State University, Fresno. Besøkt 13. februar 2012.

- ^ Geissler, Paul E.; Greenberg, Richard; m.fl. (1998). «Evolution of Lineaments on Europa: Clues from Galileo Multispectral Imaging Observations». Besøkt 20. desember 2007.

- ^ Figueredo, Patricio H.; and Greeley, Ronald (2003). «Resurfacing history of Europa from pole-to-pole geological mapping». Besøkt 20. desember 2007.

- ^ Hurford, Terry A.; Sarid, Alyssa R.; and Greenberg, Richard (2006). «Cycloidal cracks on Europa: Improved modeling and non-synchronous rotation implications». Besøkt 20. desember 2007.

- ^ Kattenhorn, Simon A. (2002). «Nonsynchronous Rotation Evidence and Fracture History in the Bright Plains Region, Europa». Icarus. 157 (2): 490–506. Bibcode:2002Icar..157..490K. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6825.

- ^ a b Sotin, Christophe; Head III, James W.; and Tobie, Gabriel (2001). «Europa: Tidal heating of upwelling thermal plumes and the origin of lenticulae and chaos melting» (PDF). Besøkt 20. desember 2007.

- ^ Goodman, Jason C.; Collins, Geoffrey C.; Marshall, John; and Pierrehumbert, Raymond T. «Hydrothermal Plume Dynamics on Europa: Implications for Chaos Formation» (PDF). Besøkt 20. desember 2007.

- ^ O'Brien, David P.; Geissler, Paul; and Greenberg, Richard; Geissler; Greenberg (2000). «Tidal Heat in Europa: Ice Thickness and the Plausibility of Melt-Through». Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 30: 1066. Bibcode:2000DPS....32.3802O.

- ^ Greenberg, Richard (2008). «Unmasking Europa».

- ^ a b Schmidt, Britney; Blankenship, Don; Patterson, Wes; Schenk, Paul (24 November 2011). «Active formation of ‘chaos terrain’ over shallow subsurface water on Europa». Nature. 479: 502–505. doi:10.1038/nature10608. Sjekk datoverdier i

|dato=(hjelp) - ^ a b Marc Airhart (2011). «Scientists Find Evidence for "Great Lake" on Europa and Potential New Habitat for Life». Jackson School of Geosciences. Besøkt 16. november 2011.

- ^ a b Greenberg, Richard; Europa: The Ocean Moon: Search for an Alien Biosphere, Springer Praxis Books, 2005

- ^ McFadden, Lucy-Ann; Weissman, Paul; and Johnson, Torrence (2007). The Encyclopedia of the Solar System. Elsevier. s. 432. ISBN 0-12-226805-9.

- ^ Greeley, Ronald; et al.; Chapter 15: Geology of Europa, in Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, Cambridge University Press, 2004

- ^ a b Billings, Sandra E. (2005). «The great thickness debate: Ice shell thickness models for Europa and comparisons with estimates based on flexure at ridges». Icarus. 177 (2): 397–412. Bibcode:2005Icar..177..397B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.03.013.

- ^ Siteringsfeil: Ugyldig

<ref>-tagg; ingen tekst ble oppgitt for referansen ved navnSchenk - ^ Zyga, Lisa (12 December 2008). «Scientist Explains Why Jupiter's Moon Europa Could Have Energetic Liquid Oceans». PhysOrg.com. Besøkt 28. juli 2009. Sjekk datoverdier i

|dato=(hjelp) - ^ Tyler, Robert H. (11 December 2008). «Strong ocean tidal flow and heating on moons of the outer planets». Nature. 456 (7223): 770–772. Bibcode:2008Natur.456..770T. PMID 19079055. doi:10.1038/nature07571. Sjekk datoverdier i

|dato=(hjelp) - ^ Zimmer, Christophe (2000). «Subsurface Oceans on Europa and Callisto: Constraints from Galileo Magnetometer Observations» (PDF). Icarus. 147 (2): 329–347. Bibcode:2000Icar..147..329Z. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6456.

- ^ Siteringsfeil: Ugyldig

<ref>-tagg; ingen tekst ble oppgitt for referansen ved navnKivelson - ^ McCord, Thomas B.; Hansen, Gary B.; m.fl. (1998). «Salts on Europa's Surface Detected by Galileo's Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer». Besøkt 20. desember 2007.

- ^ Carlson, Robert W.; Anderson, Mark S.; Mehlman, Robert; and Johnson, Robert E. (2005). «Distribution of hydrate on Europa: Further evidence for sulfuric acid hydrate». Besøkt 20. desember 2007.

- ^ Calvin, Wendy M. (1995). «Spectra of the ice Galilean satellites from 0.2 to 5 µm: A compilation, new observations, and a recent summary». Journal of Geophysical Research. 100 (E9): 19,041–19,048. Bibcode:1995JGR...10019041C. doi:10.1029/94JE03349.

- ^ Hall, Doyle T.; et al.; Detection of an oxygen atmosphere on Jupiter's moon Europa, Nature, Vol. 373 (23 February 1995), pp. 677–679 (accessed 15 April 2006)

- ^ Savage, Donald (23. februar 1995). «Hubble Finds Oxygen Atmosphere on Europa». Project Galileo. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Besøkt 17. august 2007.

- ^ Siteringsfeil: Ugyldig

<ref>-tagg; ingen tekst ble oppgitt for referansen ved navnMcGrathChapter - ^ Kliore, Arvydas J. (1997). «The Ionosphere of Europa from Galileo Radio Occultations». Science. 277 (5324): 355–358. Bibcode:1997Sci...277..355K. PMID 9219689. doi:10.1126/science.277.5324.355. Besøkt 10. august 2007.

- ^ «Galileo Spacecraft Finds Europa has Atmosphere». Project Galileo. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 1997. Besøkt 10. august 2007.

- ^ Johnson, Robert E.; Lanzerotti, Louis J.; and Brown, Walter L.; Lanzerotti; Brown (1982). «Planetary applications of ion induced erosion of condensed-gas frosts». Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research. 198: 147. Bibcode:1982NucIM.198..147J. doi:10.1016/0167-5087(82)90066-7.

- ^ Shematovich, Valery I.; Cooper; Johnson (2003). «Surface-bounded oxygen atmosphere of Europa». EGS - AGU - EUG Joint Assembly (Abstracts from the meeting held in Nice, France): 13094. Bibcode:2003EAEJA....13094S.

- ^ Liang, Mao-Chang (2005). «Atmosphere of Callisto» (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 110 (E2): E02003. Bibcode:2005JGRE..11002003L. doi:10.1029/2004JE002322.

- ^ Smyth, William H. (August 15, 2007). «Processes Shaping Galilean Satellite Atmospheres from the Surface to the Magnetosphere» (pdf). Abstracts. Workshop on Ices, Oceans, and Fire: Satellites of the Outer Solar System, Boulder, Colorado. Sjekk datoverdier i

|dato=(hjelp) - ^ Chyba, Christopher F.; and Hand, Kevin P.; Life without photosynthesis

- ^ a b Hand, Kevin P.; Carlson, Robert W.; Chyba, Christopher F. (2007). «Energy, Chemical Disequilibrium, and Geological Constraints on Europa». Astrobiology. 7 (6): 1006–1022. Bibcode:2007AsBio...7.1006H. PMID 18163875. doi:10.1089/ast.2007.0156.

- ^ Smyth, William H. (2006). «Europa's atmosphere, gas tori, and magnetospheric implications». Icarus. 181 (2): 510. Bibcode:2006Icar..181..510S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.10.019.

- ^ Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; and Irwin, Louis N. (2001). «Alternative Energy Sources Could Support Life on Europa» (PDF). Departments of Geological and Biological Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso. Arkivert fra originalen (PDF) July 3, 2006. Besøkt 21. desember 2007. Sjekk datoverdier i

|arkivdato=(hjelp) - ^ Exotic Microbes Discovered near Lake Vostok, Science@NASA (December 10, 1999)

- ^ Siteringsfeil: Ugyldig

<ref>-tagg; ingen tekst ble oppgitt for referansen ved navnEuropaLife - ^ Jones, Nicola; Bacterial explanation for Europa's rosy glow, NewScientist.com (11 December 2001)

- ^ Phillips, Cynthia; Time for Europa, Space.com (28 September 2006)

- ^ a b Chamberlin, Sean (1999). «Creatures Of The Abyss: Black Smokers and Giant Worms». Fullerton College. Besøkt 21. desember 2007. [død lenke]

- ^ Wilson, Colin P. (2007). «Tidal Heating on Io and Europa and its Implications for Planetary Geophysics». Geology and Geography Dept., Vassar College. Besøkt 21. desember 2007.

- ^ McCollom, Thomas M. (1999). «Methanogenesis as a potential source of chemical energy for primary biomass production by autotrophic organisms in hydrothermal systems on Europa». Journal of Geophysical Research. 104: 30729. Bibcode:1999JGR...10430729M. doi:10.1029/1999JE001126. Både

|verk=og|publikasjon=er angitt. Kun én av dem skal angis. (hjelp) - ^ a b Marion, Giles M.; Fritsen, Christian H.; Eicken, Hajo; and Payne, Meredith C. (2003). «The Search for Life on Europa: Limiting Environmental Factors, Potential Habitats, and Earth Analogues». Astrobiology. Besøkt 21. desember 2007.

- ^ Nancy Atkinson (2009). «Europa Capable of Supporting Life, Scientist Says». Universe Today. Besøkt 11. oktober 2009.

Litteratur

- Litteratur til artikkelen

- Bills, Bruce G. (2005). «Free and forced obliquities of the Galilean satellites of Jupiter». Icarus (engelsk) (1 utg.). 175. Bibcode:2005Icar..175..233B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.10.028.

- Geissler, P.E.; Greenberg, R.; Hoppa, G.; Helfenstein, P.; McEwen, A.; Pappalardo, R.; Tufts, R.; Ockert-Bell, M.; Sullivan, R.; Greeley, R.; Belton, M. J. S.; Denk, T.; Clark, B. E.; Burns, J.; Veverka, J. «Evidence for non-synchronous rotation of Europa». Nature (engelsk) (6665 utg.). 391. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..368G. PMID 9450751. doi:10.1038/34869. Parameteren

|ugivelsesår=støttes ikke av malen. (hjelp) - Jeffrey S. Kargel, Jonathan Z. Kaye, James W. Head, III; m.fl. (2000). «Europa's Crust and Ocean: Origin, Composition, and the Prospects for Life» (PDF). Icarus (engelsk) (1 utg.). 148. Bibcode:2000Icar..148..226K. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6471. Både

|verk=og|publikasjon=er angitt. Kun én av dem skal angis. (hjelp) - Kivelson, Margaret G.; Khurana, Krishan K.; Russell, Christopher T.; Volwerk, Martin; Walker, Raymond J.; Zimmer, Christophe (2000). «Galileo Magnetometer Measurements: A Stronger Case for a Subsurface Ocean at Europa». Science (engelsk) (5483 utg.). 289. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1340K. PMID 10958778. doi:10.1126/science.289.5483.1340.

- Marazzini, Claudio (2005). «I nomi dei satelliti di Giove: da Galileo a Simon Marius (The names of the satellites of Jupiter: from Galileo to Simon Marius)». Lettere Italiane (engelsk) (3 utg.). 57.

- McFadden, Lucy-Ann; Weissman, Paul; and Johnson, Torrence (2007). The Encyclopedia of the Solar System (engelsk). Elsevier. ISBN 0-12-226805-9.

- McGrath (2009). «Atmosphere of Europa». I Pappalardo, Robert T.; McKinnon, William B.; og Khurana, Krishan K. Europa (engelsk). University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-2844-6.

- Schenk, Paul M.; Chapman, Clark R.; Zahnle, Kevin; Moore, Jeffrey M. (2004). «18: Ages and Interiors: the Cratering Record of the Galilean Satellites». Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere (engelsk). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521818087.

- Showman, Adam P.; Malhotra, Renu (1997). «Tidal Evolution into the Laplace Resonance and the Resurfacing of Ganymede» (PDF). Icarus (engelsk) (1 utg.). 127. Bibcode:1997Icar..127...93S. doi:10.1006/icar.1996.5669.

- Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip J. (1962). The Effects of Nuclear Weapons (engelsk) (rev utg.). USAs forsvarsdepartement.

- Øvrig litteratur

- Bagenal, Fran; Dowling, Timothy Edward; McKinnon, William B. (2004). Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere (engelsk). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81808-7.

- Rothery, David A. (1999). Satellites of the Outer Planets: Worlds in Their Own Right (engelsk). Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-512555-X.

- Harland, David M. (2000). Jupiter Odyssey: The Story of NASA's Galileo Mission (engelsk). Springer. ISBN 1-85233-301-4.

- Greenberg, Richard (2005). EUROPA The Ocean Moon (engelsk). Springer. ISBN 3-540-22450-5.

Eksterne lenker

- Europa, a Continuing Story of Discovery hos NASA/JPL (engelsk)

- Europa Profile hos NASA's Solar System Exploration site (engelsk)

- Astronomy Cast: Europa. Frasier Cain, 2010 (engelsk)

- Europa page hos The Nine Planets (engelsk)

- Europa page hos Views of the Solar System (engelsk)

- The Calendars of Jupiter (engelsk)

- Are our nearest living neighbours on one of Jupiter's Moons? (engelsk)

- Preventing Forward Contamination of Europa - SSB Study of Planetary (engelsk)

- Protection policies for Europa (engelsk)

- Images of Europa at JPL's Planetary Photojournal (engelsk)

- Film av Europas rotasjon fra the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (engelsk)

- Europa map with feature names fra Planetary Photojournal (engelsk)

- Europa nomenclature og Europa map with feature names fra USGS planetary nomenclature page (engelsk)

- Paul Schenk's 3D images and flyover videos of Europa and other outer solar system satellites; (engelsk) see also (engelsk)

- Large, high-resolution Galileo image mosaics of Europan terrain from Jason (engelsk) Perry's (normally Io-related) blog: (engelsk) 1, 2, 3, 4, (engelsk) 5, 6, (engelsk) 7 (engelsk)

- Europa image montage from Galileo spacecraft, NASA APOD (engelsk)

Siteringsfeil: <ref>-merker finnes for gruppenavnet «lower-alpha», men ingen <references group="lower-alpha"/>-merking ble funnet

Siteringsfeil: <ref>-merker finnes for gruppenavnet «S», men ingen <references group="S"/>-merking ble funnet