Karbonavgift til fordeling: Forskjell mellom sideversjoner

ferdig med avskoging for nå |

Ny runde |

||

| Linje 1: | Linje 1: | ||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2011}} |

|||

{{chembox |

|||

| Watchedfields = changed |

|||

| verifiedrevid = 443668448 |

|||

| Name = Bisphenol A |

|||

| ImageFile1_Ref = {{chemboximage|correct|??}} |

|||

| ImageFile1 = Bisphenol A.svg |

|||

| ImageSize1 = 240px |

|||

| ImageFile2 = Bisphenol A.png |

|||

| ImageSize2 = 180px |

|||

| ImageName = Bisphenol A |

|||

| IUPACName = 4,4'-(propane-2,2-diyl)diphenol |

|||

| OtherNames = BPA, ''p'',''p'''-isopropylidenebisphenol,<br /> 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)propane. |

|||

| Section1 = {{Chembox Identifiers |

|||

| ChEBI_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} |

|||

| ChEBI = 33216 |

|||

| DrugBank_Ref = {{drugbankcite|correct|drugbank}} |

|||

| DrugBank = DB06973 |

|||

| SMILES = Oc1ccc(cc1)C(c2ccc(O)cc2)(C)C |

|||

| UNII_Ref = {{fdacite|correct|FDA}} |

|||

| UNII = MLT3645I99 |

|||

| KEGG_Ref = {{keggcite|correct|kegg}} |

|||

| KEGG = C13624 |

|||

| InChI = 1/C15H16O2/c1-15(2,11-3-7-13(16)8-4-11)12-5-9-14(17)10-6-12/h3-10,16-17H,1-2H3 |

|||

| InChIKey = IISBACLAFKSPIT-UHFFFAOYAI |

|||

| SMILES1 = CC(C)(c1ccc(cc1)O)c2ccc(cc2)O |

|||

| ChEMBL_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} |

|||

| ChEMBL = 418971 |

|||

| StdInChI_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} |

|||

| StdInChI = 1S/C15H16O2/c1-15(2,11-3-7-13(16)8-4-11)12-5-9-14(17)10-6-12/h3-10,16-17H,1-2H3 |

|||

| StdInChIKey_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} |

|||

| StdInChIKey = IISBACLAFKSPIT-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

|||

| CASNo = 80-05-7 |

|||

| CASNo_Ref = {{cascite|correct|CAS}} |

|||

| PubChem = 6623 |

|||

| EINECS = 201-245-8 |

|||

| ChemSpiderID_Ref = {{chemspidercite|correct|chemspider}} |

|||

| ChemSpiderID = 6371 |

|||

| RTECS = SL6300000 |

|||

| UNNumber = 2430 |

|||

}} |

|||

| Section2 = {{Chembox Properties |

|||

| C=15|H=16|O=2 |

|||

| Appearance = White solid |

|||

| Density = 1.20 g/cm³ |

|||

| Solubility = 120–300 ppm (21.5 °C) |

|||

| MeltingPtCL = 158 |

|||

| MeltingPtCH = 159 |

|||

| BoilingPtC = 220 |

|||

| Boiling_notes = 4 mmHg |

|||

| Viscosity = |

|||

}} |

|||

| Section3 = {{Chembox Structure |

|||

| CrystalStruct = |

|||

| Dipole = |

|||

}} |

|||

| Section7 = {{Chembox Hazards |

|||

| ExternalMSDS = |

|||

| EUIndex = |

|||

| EUClass = |

|||

| NFPA-H = 3 |

|||

| NFPA-F = 0 |

|||

| NFPA-R = 0 |

|||

| RPhrases = {{R36}} {{R37}} {{R38}} {{R43}} |

|||

| SPhrases = {{S24}} {{S26}} {{S37}} |

|||

| FlashPt = {{convert|227|C|F}} |

|||

| autoignition = {{convert|600|C|F}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| Section8 = {{Chembox Related |

|||

| Function = |

|||

| OtherFunctn = |

|||

| OtherCpds = [[phenols]]<br />[[Bisphenol S]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Bisfenol A''' ('''BPA''') er et [[organisk stoff]] med [[kjemisk formel]] (CH<sub>3</sub>)<sub>2</sub>C(C<sub>6</sub>H<sub>4</sub>OH)<sub>2</sub>. Det er et fargeløst fast stoff som er løselig i en organisk løsning men lite løselig i vann. Having two [[phenol]] [[functional group]]s, it is used to make [[polycarbonate]] polymers and [[epoxy resins]], along with other materials used to make [[plastic]]s. |

|||

BPA is controversial because it exerts weak but detectable hormone-like properties, raising concerns about its presence in consumer products. Starting in 2008, several governments questioned its safety, prompting some retailers to withdraw polycarbonate products. A 2010 report from the United States [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA) raised further concerns regarding exposure of fetuses, infants and young children.<ref name="U.S. Food and Drug Administration">{{cite web|url=http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm197739.htm|title=Update on Bisphenol A for Use in Food Contact Applications: January 2010 |date=15 January 2010 |publisher=[[U.S. Food and Drug Administration]]|accessdate=15 January 2010}}</ref> In September 2010, Canada became the first country to declare BPA a toxic substance.<ref>{{Cite journal |url=http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2010/2010-10-13/pdf/g2-14421.pdf |journal=[[Canada Gazette]] Part II |volume=144 |issue=21 |date=13 October 2010 |pages=1806–18 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/canada-first-to-declare-bisphenol-a-toxic/article1755272/ |title=Canada first to declare bisphenol A toxic |author=Martin Mittelstaedt |work=The Globe and Mail |location=Canada |date=13 October 2010}}</ref> In the [[European Union]] and Canada, BPA use is banned in baby bottles.<ref name="rban2011"/> |

|||

==Production== |

|||

World production capacity of this compound was 1 million tons in the 1980s,<ref name = Fiege/> and more than 2.2 million tons in 2009.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE65L6JN20100622?loomia_ow=t0:s0:a49:g43:r3:c0.084942:b35124310:z0|title=Experts demand European action on plastics chemical|publisher=Reuters | date=22 June 2010}}</ref> In 2003, U.S. consumption was 856,000 tons, 72% of which was used to make polycarbonate plastic and 21% going into epoxy resins.<ref name="CERHR"/> In the US, less than 5% of the BPA produced is used in food contact applications<ref name="epa-action-plan"/> but remains in the canned food industry.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine-archive/december-2009/food/bpa/overview/bisphenol-a-ov.htm|publisher=Consumer Reports|date=December 2009}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.foxnews.com/health/2011/11/23/soaring-bpa-levels-found-in-people-who-eat-canned-foods/|publisher=Fox News|date=23 November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

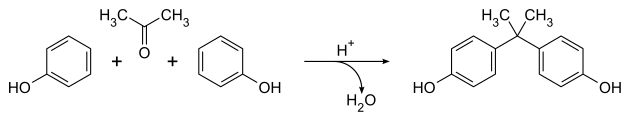

Bisphenol A was first synthesized by the [[Russia]]n [[chemist]] [[A.P. Dianin]] in 1891.<ref name=dianin>{{Cite journal | author=Dianin | title = Zhurnal russkogo fiziko-khimicheskogo obshchestva | volume = 23 | year = 1891 | pages = 492–}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | first = Theodor | last = Zincke | authorlink = Theodor Zincke | title = Ueber die Einwirkung von Brom und von Chlor auf Phenole: Substitutionsprodukte, Pseudobromide und Pseudochloride | journal=[[Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie]] | year = 1905 | pages = 75–99 | doi = 10.1002/jlac.19053430106 | volume = 343}}</ref> This compound is synthesized by the [[condensation reaction|condensation]] of [[acetone]] (hence the suffix A in the name)<ref>{{Cite book | last=Uglea | first=Constantin V. | coauthors=Ioan I. Negulescu | title=Synthesis and Characterization of Oligomers | year=1991 | publisher=[[CRC Press]] | page=103 | isbn=0849349540}}</ref> with two [[Equivalent (chemistry)|equivalents]] of [[phenol]]. The reaction is [[catalysis|catalyzed]] by a strong acid, such as [[hydrochloric acid]] (HCl) or a [[Sodium polystyrene sulfonate|sulfonated polystyrene resin]]. Industrially, a large excess of phenol is used to ensure full condensation; the product mixture of the [[cumene process]] (acetone and phenol) may also be used as starting material:<ref name=Fiege/> |

|||

:[[File:Synthesis Bisphenol A.svg|frameless|upright=2.5|Synthesis of bisphenol A from phenol and acetone]] |

|||

A large number of [[ketone]]s undergo analogous condensation reactions. Commercial production of BPA requires distillation – either extraction of BPA from many resinous byproducts under [[high vacuum]], or solvent-based extraction using additional phenol followed by distillation.<ref name=Fiege>{{Cite book | first = Helmut | last = Fiege | coauthors = Heinz-Werner Voges, Toshikazu Hamamoto, Sumio Umemura, Tadao Iwata, Hisaya Miki, Yasuhiro Fujita, Hans-Josef Buysch, Dorothea Garbe, Wilfried Paulus | title = Phenol Derivatives | series = Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry | publisher=Wiley-VCH | location = Weinheim | year = 2002 | doi = 10.1002/14356007.a19_313}}</ref> |

|||

==Use== |

|||

{{further|[[Polycarbonate]]}} |

|||

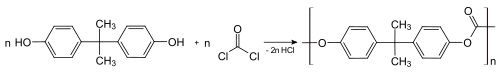

Bisphenol A is used primarily to make plastics, and products using bisphenol A-based plastics have been in commerce use since 1957.<ref name="infosheet">{{cite web | title=Bisphenol A Information Sheet | date=October 2002 | publisher=Bisphenol A Global Industry Group | url=http://www.bisphenol-a.org/pdf/DiscoveryandUseOctober2002.pdf | accessdate=7 December 2010 }}</ref> At least 8 billion pounds of BPA are used by manufacturers yearly.<ref name="USNews3">{{Cite news|url=http://health.usnews.com/health-news/family-health/heart/articles/2009/06/10/studies-report-more-harmful-effects-from-bpa.html|title=Studies Report More Harmful Effects From BPA|date=10 June 2009|work=[[U.S. News & World Report]]|accessdate=28 October 2010}}</ref> It is a key [[monomer]] in production of [[epoxy]] resins<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.californiaprogressreport.com/2009/07/committee_succe.html|title=Lawmakers to press for BPA regulation|last=Replogle|first=Jill|date=17 July 2009|publisher=California Progress Report|accessdate=2 August 2009}} {{Dead link|date=September 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.thestar.com/article/415296|title=Ridding life of bisphenol A a challenge|last=Ubelacker |first=Sheryl |date=16 April 2008|work=Toronto Star |accessdate=2 August 2009}}</ref> and in the most common form of [[polycarbonate]] [[plastic]].<ref name=Fiege/><ref>{{Cite book|last=Kroschwitz|first=Jacqueline I.|title=Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology|edition=5|volume=5|page=8|isbn=0471526959}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.alliancepoly.com/polycarbonate.asp|title=Polycarbonate (PC) Polymer Resin|publisher=Alliance Polymers, Inc|accessdate=2 August 2009}}</ref> The overall reaction to give polycarbonate can be written: |

|||

:[[File:Polycarbonatsynthese.svg|500px]] |

|||

Polycarbonate plastic, which is clear and nearly shatter-proof, is used to make a variety of common products including baby and water bottles, sports equipment, medical and dental devices, [[dental fillings]] and sealants, CDs and DVDs, household electronics, and eyeglass lenses.<ref name=Fiege/> BPA is also used in the synthesis of [[polysulfone]]s and [[polyether]] [[ketones]], as an [[antioxidant]] in some [[plasticizer]]s, and as a [[polymerization]] inhibitor in [[Polyvinyl chloride|PVC]]. Epoxy resins containing bisphenol A are used as coatings on the inside of almost all food and [[beverage can]]s,<ref name="C&ENews">{{Cite journal|last=Erickson|first=Britt E.|date=2 June 2008|title=Bisphenol A under scrutiny|journal=Chemical and Engineering News|publisher=American Chemical Society|volume=86|issue=22|pages=36–39|url=http://pubs.acs.org/isubscribe/journals/cen/86/i22/html/8622gov1.html}}</ref> however, due to BPA health concerns, in Japan epoxy coating was mostly replaced by [[PET film (biaxially oriented)|PET film]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.foodnavigator.com/Financial-Industry/Consumers-fear-the-packaging-a-BPA-alternative-is-needed-now|title=Consumers fear the packaging - a BPA alternative is needed now|last=Byrne|first=Jane|date=22 September 2008|accessdate=5 January 2010}}</ref> Bisphenol A is also a precursor to the [[flame retardant]] [[tetrabromobisphenol A|tetrabromobisphenol A]], and was formerly used as a [[fungicide]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://pesticideinfo.org/Detail_Chemical.jsp?Rec_Id=PC33756 |title=Bisphenol A |publisher=Pesticideinfo.org |date= |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> Bisphenol A is a preferred color developer in [[carbonless copy paper]] and [[thermal paper]],<ref>{{Cite patent|US|6562755}}</ref> with the most common public exposure coming from some<ref>{{cite web|title=More evidence that BPA laces store receipts|url=http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/61490/title/Science_%2B_the_Public__More_evidence_that_BPA_laces_store_receipts|quote=Bill Van Den Brandt of Appleton Papers says that the receipts paper made by his company (which bills itself as the nation's leading producer of carbonless and thermal papers) is BPA-free.|date=27 July 2001|accessdate=3 August 2010|author=Raloff, Janet|publisher=Science News}}</ref> thermal [[point of sale]] receipt paper.<ref>{{cite web|title=Concerned about BPA: Check your receipts|url=http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/48084/title/Science_%2B_the_Public__Concerned_about_BPA_Check_your_receipts|date=7 October 2009|accessdate=3 August 2010|author=Raloff, Janet|publisher=Science News}}</ref><ref name="ReferenceA">{{Cite doi|10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00507-5}}</ref> BPA-based products are also used in [[Foundry|foundry castings]] and for lining water pipes.<ref name="epa-action-plan">{{cite web|url=http://www.epa.gov/oppt/existingchemicals/pubs/actionplans/bpa_action_plan.pdf|title=Bisphenol A Action Plan |date=29 March 2010|publisher=U.S. Environmental Protection Agency|accessdate=12 April 2010}}</ref> |

|||

===Identification in plastics=== |

|||

{{Main|Resin identification code}} |

|||

[[Image:Plastic-recyc-07.svg|thumb|100px|Some [[Plastic identification code#Plastic identification code|type 7]] plastics may leak bisphenol A|left]] |

|||

[[Image:Plastic-recyc-03.svg|thumb|100px|Flexible [[Plastic identification code#Plastic identification code|type 3]] plastics may leak bisphenol A|right]] |

|||

"In general, plastics that are marked with recycle codes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 are very unlikely to contain BPA. Some, but not all, plastics that are marked with recycle codes 3 or 7 may be made with BPA."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hhs.gov/safety/bpa/ |title=Bisphenol A (BPA) Information for Parents |publisher=Hhs.gov |date=2010-01-15 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

There are [[Plastic identification code#Plastic identification code|seven classes of plastics]] used in packaging applications. Type 7 is the catch-all "other" class, and some type 7 plastics, such as [[polycarbonate]] (sometimes identified with the letters "PC" near the [[recycling symbol]]) and epoxy resins, are made from bisphenol A monomer.<ref name=Fiege/><!--When such plastics are exposed to hot liquids, bisphenol A leaks out 55 times faster than it does under normal conditions.{{Clarify|date=March 2009}}--><!-- Unit incomplete. Nanogrammes per hour per how much of the plastic? That much per mg would be a lot, per tonne not much. Also need to know what "hot" means, and what "normal conditions" means.--><ref name="sciam2008">{{Cite journal|author=Biello D | title=Plastic (not) fantastic: Food containers leach a potentially harmful chemical | journal=Scientific American | volume=2 | date=19 February 2008 | url=http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=plastic-not-fantastic-with-bisphenol-a | accessdate=9 April 2008}}</ref> |

|||

Type 3 ([[PVC]]) can also contain bisphenol A as an antioxidant in [[plasticizers]].<ref name=Fiege/> This refers to "flexible PVC", but not for rigids such as pipe, windows and siding. |

|||

{{Clear}} |

|||

==Health effects== |

|||

Bisphenol A is an [[endocrine disruptor]], which can mimic the body's own [[hormones]] and may lead to negative health effects.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Gore|first=Andrea C. |title=Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: From Basic Research to Clinical Practice|publisher=Humana Press|date=8 June 2007|series=Contemporary Endocrinology|isbn=978-1588298300}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=O’Connor |first1=JC |last2=Chapin |first2=RE | title = Critical evaluation of observed adverse effects of endocrine active substances on reproduction and development, the immune system, and the nervous system | journal=Pure Appl. Chem | volume = 75 | issue = 11–12 | pages = 2099–2123 |year=2003 | url = http://www.iupac.org/publications/pac/2003/pdf/7511x2099.pdf| format = Full Article | accessdate = 28 February 2007 | doi = 10.1351/pac200375112099}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |author=Okada H, Tokunaga T, Liu X, Takayanagi S, Matsushima A, Shimohigashi Y |title=Direct evidence revealing structural elements essential for the high binding ability of bisphenol A to human estrogen-related receptor-gamma |journal=Environ. Health Perspect. |volume=116 |issue=1 |pages=32–8 |year=2008 |month=January |pmid=18197296 |pmc=2199305 |doi=10.1289/ehp.10587 |url=}}</ref><ref name=JAMAVS>{{Cite journal |author=vom Saal FS, Myers JP |title=Bisphenol A and Risk of Metabolic Disorders |journal=[[Journal of the American Medical Association|JAMA]] |volume= 300|issue= 11|pages= 1353–5|year=2008 |pmid= 18799451|doi=10.1001/jama.300.11.1353 |url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/300.11.1353}}</ref> Early development appears to be the period of greatest sensitivity to its effects,<ref name=HealthCanada>[http://www.ec.gc.ca/substances/ese/eng/challenge/batch2/batch2_80-05-7.cfm Draft Screening Assessment for The Challenge Phenol, 4,4' -(1-methylethylidene)bis- (Bisphenol A)Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number 80-05-7.] [[Health Canada]], 2008.</ref> and some studies have linked prenatal exposure to later neurological difficulties. Regulatory bodies have determined safety levels for humans, but those safety levels are currently being questioned or under review as a result of new scientific studies.<ref name=EHP>{{Cite journal |author=Ginsberg G, Rice DC |title=Does Rapid Metabolism Ensure Negligible Risk from Bisphenol A?|journal=[[Environmental Health Perspectives|EPH]] |volume= 117|issue=11 |pages=1639–1643|year=2009 |doi=10.1289/ehp.0901010 |url=http://www.ehponline.org/members/2009/0901010/0901010.html |pmid=20049111 |pmc=2801165}}</ref><ref>{{Cite pmid|19931376}}</ref> A 2011 study that investigated the number of chemicals pregnant women are exposed to in the U.S. found BPA in 96% of women.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/01/110114081653.htm |title=99% of pregnant women in US test positive for multiple chemicals including banned ones, study suggests |doi=10.1289/ehp.1002727 |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2011-01-14 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

In 2009, [[The Endocrine Society]] released a statement expressing concern over current human exposure to BPA.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.endocrinetoday.com/view.aspx?rid=40865 |title=Endocrine Society released scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals |publisher=Endocrinetoday.com |date=2009-06-11 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

In 2011, the [[Food Standards Agency]]'s chief scientist said "the evidence [is] that BPA is rapidly absorbed, detoxified, and eliminated from humans – therefore is not a health concern."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://blogs.food.gov.uk/science/entry/small_pond_same_big_issues |title=Small pond, same big issues |publisher=[[Food Standards Agency|FSA]] |first=Andrew |last=Wage |date=27 July 2011 |accessdate=3 August 2011 }}</ref> |

|||

===Expert panel conclusions=== |

|||

In 2007, a consensus statement by 38 experts on bisphenol A concluded that average levels in people are above those that cause harm to many animals in laboratory experiments. However, they noted that while BPA is not persistent in the environment or in humans, [[biomonitoring]] surveys indicate that exposure is continuous, which is problematic because acute animal exposure studies are used to estimate daily human exposure to BPA, and no studies that had examined BPA [[pharmacokinetics]] in animal models had followed continuous low-level exposures. They added that measurement of BPA levels in serum and other body fluids suggests that either BPA intake is much higher than accounted for, or that BPA can bioaccumulate in some conditions such as pregnancy, or both.<ref>{{Cite journal |author=vom Saal FS |title=Chapel Hill bisphenol A expert panel consensus statement: integration of mechanisms, effects in animals and potential to impact human health at current levels of exposure |journal=Reprod. Toxicol. |volume=24 |issue=2 |pages=131–8 |year=2007 |pmid=17768031 |pmc=2967230 |doi=10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.07.005 |url= |author-separator=, |author2=Akingbemi BT |author3=Belcher SM |display-authors=3 |last4=Birnbaum |first4=Linda S. |last5=Crain |first5=D. Andrew |last6=Eriksen |first6=Marcus |last7=Farabollini |first7=Francesca |last8=Guillette |first8=Louis J. |last9=Hauser |first9=Russ}}</ref> A 2011 study, the first to examine BPA in a continuous low-level exposure throughout the day, did find an increased absorption and accumulation of BPA in the blood of mice.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/06/110606075708.htm |title=Bisphenol A (BPA) accumulates more rapidly within the body than previously thought |doi=10.1289/ehp.1003385 |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2011-06-06 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

In 2007 it was reported that among government-funded BPA experiments on lab animals and tissues, 153 found adverse effects and 14 did not, whereas all 13 studies funded by chemical corporations reported no harm. Assessment of potential impact on human health involves measurement of residual BPA in the products and quantitative study of its ease of separation from the product, passage into the human body and residence time and location there. |

|||

The studies indicating harm reported a variety of deleterious effects in rodent offspring exposed in the womb: abnormal weight gain, insulin resistance, prostate cancer, and excessive mammary gland development.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://pubs.acs.org/cen/government/85/8516gov2.html |title=Chemical & Engineering News: Government & Policy - Bisphenol A On Trial |publisher=Pubs.acs.org |date= |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

A panel convened by the U.S. [[National Institutes of Health]] in 2007 determined that there was "some concern" about BPA's effects on fetal and infant brain development and behavior.<ref name="CERHR"/> The concern over the effect of BPA on infants was also heightened by the fact that infants and children are estimated to have the highest daily intake of BPA.<ref>[http://www.center4research.org/2010/04/are-bisphenol-a-bpa-plastic-products-safe-for-infants-and-children/ Are BPA Products Safe for Infants and Children?], National Research Center for Women and Families Website.</ref> A 2008 report by the U.S. [[National Toxicology Program]] (NTP) later agreed with the panel, expressing "some concern for effects on the brain, behavior, and prostate gland in fetuses, infants, and children at current human exposures to bisphenol A," and "''minimal'' concern for effects on the mammary gland and an earlier age for puberty for females in fetuses, infants, and children at current human exposures to bisphenol A." The NTP had "''negligible'' concern that exposure of pregnant women to bisphenol A will result in fetal or neonatal mortality, birth defects, or reduced birth weight and growth in their offspring."<ref name=NTP08>[http://www.niehs.nih.gov/news/media/questions/sya-bpa.cfm Since you asked - Bisphenol A: Questions and Answers about the Draft National Toxicology Program Brief on Bisphenol A], National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences website.</ref> |

|||

===Obesity=== |

|||

A 2008 review has concluded that obesity may be increased as a function of BPA exposure, which "...merits concern among scientists and public health officials."<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1097/MED.0b013e32830ce95c}}</ref> A 2009 review of available studies has concluded that "perinatal BPA exposure acts to exert persistent effects on body weight and adiposity".<ref>{{Cite pmid|19433248}}</ref> Another 2009 review has concluded that "Eliminating exposures to (BPA) and improving nutrition during development offer the potential for reducing obesity and associated diseases".<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.025}}</ref> Other reviews have come with similar conclusions.<ref>{{Cite pmid|19433252}}</ref><ref>{{Cite pmid|19433244}}</ref> A later study on rats has suggested that perinatal exposure to drinking water containing 1 mg/L of BPA increased adipogenesis in females at weaning.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1289/ehp.11342}}</ref> Other study suggested that larger size-for-age was due to a faster growth rate rather than obesity<ref>{{Cite pmid|20351315}}</ref> |

|||

===Neurological issues=== |

|||

A panel convened by the U.S. [[National Institutes of Health]] determined that there was "some concern" about BPA's effects on fetal and infant brain development and behavior.<ref name="CERHR"/> A 2008 report by the U.S. [[National Toxicology Program]] (NTP) later agreed with the panel, expressing "some concern for effects on the brain".<ref name=NTP08/> In January 2010 the FDA expressed the same level of concern. |

|||

A 2007 review has concluded that BPA, like other xenoestrogens, should be considered as a player within the nervous system that can regulate or alter its functions through multiple pathways.<ref>{{Cite pmid|17868795}}</ref> A 2007 review has concluded that low doses of BPA during development have persistent effects on brain structure, function and behavior in rats and mice.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.06.004}}</ref> A 2008 review concluded that low-dose BPA maternal exposure causes long-term consequences at the level of neurobehavioral development in mice.<ref>{{Cite pmid|18949834}}</ref> A 2008 review has concluded that neonatal exposure to Bisphenol-A (BPA) can affect sexually dimorphic brain morphology and neuronal adult phenotypes in mice.<ref>{{Cite pmid|17822772}}</ref> A 2008 review has concluded that BPA altered [[long-term potentiation]] in the [[hippocampus]] and even nanomolar dosage could induce significant effects on memory processes.<ref>{{Cite pmid|17822775}}</ref> A 2009 review raised concerns about BPA effect on [[anteroventral periventricular nucleus]].<ref>10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.02.002</ref> |

|||

A 2008 study by the [[Yale School of Medicine]] demonstrated that adverse neurological effects occur in [[primates|non-human primates]] regularly exposed to bisphenol A at levels equal to the [[United States Environmental Protection Agency]]'s (EPA) maximum safe dose of 50 µg/kg/day.<ref name="pmid18768812">{{Cite journal |author=Leranth C, Hajszan T, Szigeti-Buck K, Bober J, Maclusky NJ |title=Bisphenol A prevents the synaptogenic response to estradiol in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of ovariectomized nonhuman primates |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume= 105|issue= 37|pages= 14187–91|year=2008 |month=September |pmid=18768812 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0806139105 |url= |pmc=2544599}}</ref><ref name="Layton2">{{Cite news|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/09/03/AR2008090303397.html?hpid=topnews|title=Chemical in Plastic Is Connected to Health Problems in Monkeys|last=Layton|first=Lindsey|date=4 September 2008|work=Washington Post |pages=A02|accessdate=6 September 2008}}</ref> This research found a connection between BPA and interference with brain cell connections vital to memory, learning and mood. |

|||

A 2010 study with rats prenatally exposed to 40 microg/kg bw BPA has concluded that [[corticosterone]] and its actions in the brain are sensitive to the programming effects of BPA.<ref>{{Cite pmid|20219646}}</ref> |

|||

====Disruption of the dopaminergic system==== |

|||

A 2005 review concluded that prenatal and neonatal exposure to BPA in mice can potentiate the central [[Dopaminergic neuron|dopaminergic systems]], resulting in the supersensitivity to the drugs-of-abuse-induced reward effects and [[hyperlocomotion]].<ref>{{Cite pmid|16045194}}</ref> |

|||

A 2008 review has concluded that BPA mimics estrogenic activity and impacts various dopaminergic processes to enhance mesolimbic dopamine activity resulting in hyperactivity, attention deficits, and a heightened sensitivity to drugs of abuse.<ref>{{Cite pmid|18555207}}</ref> |

|||

A 2009 study on rats has concluded that prenatal and neonatal exposure to low-dose BPA causes deficits in development at dorsolateral [[striatum]] via altering the function of dopaminergic receptors.<ref>{{Cite pmid|19162132}}</ref> Another 2009 study has found associated changes in the dopaminergic system.<ref name="Tanida">{{Cite pmid|19481886}}</ref> |

|||

===Thyroid function=== |

|||

A 2007 review has concluded that bisphenol-A has been shown to bind to thyroid hormone receptor and perhaps have selective effects on its functions.<ref>{{Cite pmid|17956155}}</ref> |

|||

A 2009 review about environmental chemicals and thyroid function raised concerns about BPA effects on [[triiodothyronine]] and concluded that "available evidence suggests that governing agencies need to regulate the use of thyroid-disrupting chemicals, particularly as such uses relate exposures of pregnant women, neonates and small children to the agents".<ref>{{Cite pmid|19625957}}</ref> |

|||

A 2009 review summarized BPA adverse effects on thyroid hormone action.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1248/jhs.55.147}}</ref> |

|||

===Cancer research=== |

|||

According to the WHO's INFOSAN, carcinogenicity studies conducted under the US National Toxicology Program, have shown increases in leukaemia and testicular interstitial cell tumours in male rats<ref name="infosan">{{cite web|url=http://www.who.int/entity/foodsafety/publications/fs_management/No_05_Bisphenol_A_Nov09_en.pdf|title=BISPHENOL A (BPA) – Current state of knowledge and future actions by WHO and FAO|date=27 November 2009|accessdate=2 December 2009}}</ref> |

|||

A 2010 review at Tufts University Medical School concluded that Bisphenol A may increase cancer risk.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1038/nrendo.2010.87}}</ref> |

|||

====Breast cancer==== |

|||

{{See|Risk factors of breast cancer#Bisphenol A}} |

|||

A 2008 review stated that "evidence from animal models is accumulating that perinatal exposure to (...) low doses of (..) BPA, alters breast development and increases breast cancer risk".<ref>{{Cite doi|10.2533/chimia.2008.406}}</ref> Another 2008 review concluded that "animal experiments and epidemiological data strengthen the hypothesis that fetal exposure to xenoestrogens may be an underlying cause of the increased incidence of breast cancer observed over the last 50 years".<ref>{{Cite pmid|18226065}}</ref> <!-- not a good source A 2009 review, funded by the "Breast Cancer Fund", has recommended "a federal ban on the manufacture, distribution and sale of consumer products containing bisphenol A".<ref>{{Cite pmid|19267127}}</ref> --> |

|||

A 2009 in vitro study has concluded that BPA is able to induce neoplastic transformation in human breast epithelial cells.<ref>{{Cite pmid|19933552}}</ref> Another 2009 study concluded that maternal oral exposure to low concentrations of BPA during lactation increases mammary carcinogenesis in a rodent model.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1289/ehp.11751}}</ref> |

|||

A 2010 study with the mammary glands of the offspring of pregnant rats treated orally with 0, 25 or 250 µg BPA/kg body weight has found that key proteins involved in signaling pathways such as cellular proliferation were regulated at the protein level by BPA.<ref>{{Cite pmid|20219716}}</ref> |

|||

A 2010 study has found that BPA may reduce sensitivity to chemotherapy treatment of specific tumors.<ref>{{Cite pmid|19796866}}</ref> |

|||

====Neuroblastoma==== |

|||

In vitro studies have suggested that BPA can promote the growth of [[neuroblastoma]] cells.<ref>{{Cite pmid|19361625}}</ref><ref>{{Cite doi|10.1016/j.etap.2007.05.003}}</ref> A 2010 in vitro study has concluded that BPA potently promotes invasion and [[metastasis]] of neuroblastoma cells through overexpression of [[MMP-2]] and [[MMP-9]] as well as downregulation of [[TIMP2]].<ref>{{Cite pmid|19956873}}</ref> |

|||

====Prostate development and cancer==== |

|||

A 1997 study in mice has found that neonatal BPA exposure of 2 μg/kg increased adult prostate weight.<ref>{{Cite pmid|9074884}}</ref> A 2005 study in mice has found that neonatal BPA exposure at 10 μg/kg disrupted the development of the fetal mouse prostate.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1073/pnas.0502544102}}</ref> |

|||

A 2006 study in rats has shown that neonatal bisphenol A exposure at 10 μg/kg levels increases prostate gland susceptibility to adult-onset precancerous lesions and hormonal carcinogenesis.<ref>{{Cite pmid|16740699}}</ref> |

|||

A 2007 in vitro study has found that BPA within the range of concentrations currently measured in human serum is associated with permanent increases in prostate size.<ref>{{Cite pmid|17589598}}</ref> A 2009 study has found that newborn rats exposed to a low-dose of BPA (10 µg/kg) increased prostate cancer susceptibility when adults.<ref>{{Cite doi| 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.023}}</ref> |

|||

====DNA methylation==== |

|||

At least one study has suggested that bisphenol A suppresses [[DNA methylation]]<ref>{{Cite book|last=Bagchi|first=Debasis|title=Genomics, Proteomics and Metabolomics in Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods, |year=2010|publisher=Wiley|page=319|isbn=0813814022}}</ref> which is linked to [[epigenetic]] changes.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1073/pnas.0703739104}}</ref> |

|||

===Reproductive system and sexual behavior research=== |

|||

A 2007 study using pregnant mice showed that BPA changes the expression of key developmental [[genes]] that form the uterus, which may impact female reproductive tract development and future fertility of female fetuses.<ref>http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/02/070215145120.htm</ref> |

|||

A series of studies made in 2009 found: |

|||

* Mouse ovary anomalies from exposure as low as 1 µg/kg, concluded that BPA exposure causes long-term adverse reproductive and carcinogenic effects if exposure occurs during prenatal critical periods of differentiation.<ref name="pmid19590677">{{Cite pmid|19590677}}</ref> |

|||

* Neonatal exposure of as low as 50 µg/kg disrupts ovarian development in mice.<ref name="pmid19535786">{{Cite pmid|19535786}}</ref><ref>[http://news.ncsu.edu/news/2009/06/wmspatisaulbparats.php Study Finds Reproductive Health Effects From Low Doses of Bisphenol-A]{{dead link|date=October 2011}}</ref><ref>{{Cite pmid|19696011}}</ref> |

|||

* Neonatal BPA exposition of as low as 50 µg/kg permanently alters the hypothalamic estrogen-dependent mechanisms that govern sexual behavior in the adult female rat.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.06.012}}</ref> |

|||

* Prenatal exposure to BPA at levels of (10 μg/kg/day) affects behavioral sexual differentiation in male monkeys.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.03.005}}</ref> |

|||

* In placental JEG3 cells ''in vitro'' BPA may reduce estrogen synthesis.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.06.853 }}</ref> |

|||

* BPA exposure disrupted the [[blood-testis barrier]] when administered to immature, but not to adult, rats.<ref>{{Cite pmid|19497385}}</ref> |

|||

* Exposure to BPA in the workplace was associated with self-reported adult male sexual dysfunction.<ref>{{cite doi | 10.1093/humrep/dep381}}</ref> |

|||

A 2009 rodent study, funded by EPA and conducted by some of its scientists, concluded that, compared with [[ethinyl estradiol]], low-dose exposures of bisphenol A (BPA) showed no effects on several reproductive functions and behavioral activities measured in female rats.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1093/toxsci/kfp266}}</ref> That study was criticized as flawed for using polycarbonate cages in the experiment (since polycarbonate contains BPA) and the claimed resistance of the rats to estradiol,<ref name="Vom2010">{{Cite doi|10.1093/toxsci/kfq048}}</ref> but that claim was contested by the authors and others.<ref name="pmid20207694">{{Cite journal | author=Gray LE, Ryan B, Hotchkiss AK, Crofton KM | title = Rebuttal of "Flawed Experimental Design Reveals the Need for Guidelines Requiring Appropriate Positive Controls in Endocrine Disruption Research" by (Vom Saal 2010) | journal=[[Toxicol Sci]] | volume = 115| issue = 2| page = 614| year = 2010 | month = March | pmid = 20207694 | doi = 10.1093/toxsci/kfq073 | issn = }}</ref> Another 2009 rodent study found that BPA exposure during pregnancy has a lasting effect on one of the genes that are responsible for uterine development and subsequent fertility in both mice and humans (HOXA10). The authors concluded, "We don't know what a safe level of BPA is, so pregnant women should avoid BPA exposure."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/06/090610124428.htm |title=Bisphenol A Exposure In Pregnant Mice Permanently Changes DNA Of Offspring |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2009-06-10 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

In a 2010 study, mice were given BPA at doses thought to be equivalent to levels currently being experienced by humans. The research showed that BPA exposure affects the earliest stages of egg production in the ovaries of the developing mouse fetuses, thus suggesting that the next generation may suffer genetic defects in such biological processes as [[mitosis]] and [[DNA]] replication. In addition, the research team noted that their study "revealed a striking down-regulation of mitotic/cell cycle genes, raising the possibility that BPA exposure immediately before meiotic entry might act to shorten the reproductive lifespan of the female" by reducing the total pool of fetal [[oocytes]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/08/100825093249.htm |title=Exposure to low doses of BPA alters gene expression in the fetal mouse ovary |doi=10.1095/biolreprod.110.084814 |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2010-08-25 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> Another 2010 study with mice concluded that BPA exposure in utero leads to permanent DNA alterations in sensitivity to estrogen.<ref>{{Cite pmid|20181937}}</ref> Also in 2010, a rodent study found that by exposing fetal mice to BPA during pregnancy and examining gene expression and DNA in the uteruses of female fetuses, BPA exposure permanently affected the uterus by decreasing regulation of gene expression. The changes caused the mice to over-respond to estrogen throughout adulthood, long after the BPA exposure, thus suggesting that early exposure to BPA genetically "programmed" the uterus to be hyper-responsive to estrogen. Extreme estrogen sensitivity can lead to fertility problems, advanced puberty, altered mammary development and reproductive function, as well as a variety of hormone-related cancers. One of the authors concluded that BPA may be similar to [[diethylstilbestrol]] that caused birth defects and cancers in young women whose mothers were given the drug during pregnancy.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/02/100225101220.htm |title=Why BPA leached from 'safe' plastics may damage health of female offspring |doi=10.1096/fj.09-140533 |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2010-02-25 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

A 2011 study using the rhesus monkey — a species that is very similar to humans in regard to pregnancy and fetal development — found that prenatal exposure to BPA causes changes in female primates' uterus development.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/06/110607121127.htm |title=Fetal exposure to BPA changes development of uterus in primates, study suggests |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2011-06-07 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> A 2011 rodent study found that male rats exposed to BPA had lower sperm counts and testosterone levels than those of unexposed males.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/06/110606092740.htm |title=BPA lowers male fertility, mouse study finds |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2011-06-06 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> A 2011 mice study found that male mice exposed to BPA became demasculinized and behaved more like females in their spatial navigational abilities. They were also less desirable to female mice.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/06/110627151712.htm |title=BPA-exposed male deer mice are demasculinized and undesirable to females, new study finds |doi=10.1073/pnas.1107958108 |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2011-06-27 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

===General research=== |

|||

At an [[Endocrine Society]] meeting in 2009, new research reported data from animals experimentally treated with BPA.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/44577/title/More_troubling_news_about_BPA |

|||

|title=More Troubling News About BPA / Science News |

|||

|publisher=www.sciencenews.org |

|||

|accessdate=11 June 2009 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> Studies presented at the group's annual meeting show BPA can affect the hearts of women, can permanently damage the DNA of mice, and appears to be entering the human body from a variety of unknown sources.<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20090611/hl_nm/us_bisphenol_2 |

|||

|title=Hormone experts worried about plastics, chemicals – Yahoo! News |

|||

|publisher=news.yahoo.com |

|||

|accessdate=11 June 2009 |

|||

}} {{Dead link|date=September 2010|bot=H3llBot}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

A 2009 ''in vitro'' study on [[cytotrophoblast]]s cells has found [[Cytotoxicity|cytoxic]] effects in exposure of BPA doses from 0.0002 to 0.2 micrograms per millilitre and concluded this finding "suggests that exposure of placental cells to low doses of BPA may cause detrimental effects, leading ''in vivo'' to adverse pregnancy outcomes such as [[preeclampsia]], intrauterine growth restriction, prematurity and pregnancy loss"<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1016/j.taap.2009.09.005}}</ref> |

|||

A 2009 study in rats concluded that BPA, at the reference safe limit for human exposure, was found to impact intestinal permeability and may represent a risk factor in female offspring for developing severe [[Colitis|colonic inflammation]] in adulthood.<ref>{{Cite pmid|20018722}}</ref> |

|||

A 2010 study on mice has concluded that [[pregnancy#Perinatal period|perinatal]] exposure to 10 micrograms/mL of BPA in drinking water enhances allergic sensitization and bronchial inflammation and responsiveness in an animal model of [[asthma]],<ref>{{Cite pmid|20123615}}</ref> and a 2011 study found that higher BPA concentrations in the urine of the pregnant women at 16 weeks were associated with wheezing, a symptom of asthma, in their babies.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/05/110501183817.htm |title=Chemical in plastic, BPA, exposure may be associated with wheezing in children |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2011-05-01 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

====Studies on humans==== |

|||

=====Lang study and heart disease===== |

|||

The first large study of health effects on humans associated with bisphenol A exposure was published in September 2008 by Iain Lang and colleagues in the ''[[Journal of the American Medical Association]]''.<ref name="Lang et al.">{{Cite journal |author=Lang IA, Galloway TS, Scarlett A, Henley WE, Depledge M, Wallace RB, Melzer D |title=Association of Urinary Bisphenol A Concentration With Medical Disorders and Laboratory Abnormalities in Adults |journal=[[Journal of the American Medical Association|JAMA]] |volume= 300|issue= 11|pages= 1303–10|year=2008 |pmid= 18799442|doi=10.1001/jama.300.11.1303 |url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/300.11.1303}}</ref><ref>[http://www.newscientist.com/channel/health/dn14739-plastic-bottle-chemical-linked-to-heart-disease.html Newscientist.com] ''Plastic bottle chemical linked to heart disease''</ref> The [[cross-sectional study]] of almost 1,500 people assessed exposure to bisphenol A by looking at levels of the chemical in urine. The authors found that higher bisphenol A levels were [[Statistically significant|significantly]] associated with [[heart disease]], [[diabetes]], and abnormally high levels of certain liver enzymes. An editorial in the same issue concludes: |

|||

:"Based on this background information, the study by Lang et al,1 while preliminary with regard to these diseases in humans, should spur US regulatory agencies to follow the recent action taken by Canadian regulatory agencies, which have declared BPA a “toxic chemical” requiring aggressive action to limit human and environmental exposures.4 Alternatively, Congressional action could follow the precedent set with the recent passage of federal legislation designed to limit exposures to another family of compounds, phthalates, also used in plastic. Like BPA,5 phthalates are detectable in virtually everyone in the United States.6 This bill moves US policy closer to the European model, in which industry must provide data on the safety of a chemical before it can be used in products."<ref name=JAMAVS/><ref>{{cite doi | 10.1001/jama.300.11.1353}}</ref> |

|||

A later similar study performed by the same group of scientists, published in January 2010, confirmed, despite of lower concentrations of BPA in the second study sample, an associated increased risk for heart disease but not for diabetes or liver enzymes. Patients with the highest levels of BPA in their urine carried a 33% increased risk of coronary heart disease.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0008673}}</ref> |

|||

=====Other studies===== |

|||

Studies have associated recurrent miscarriage with BPA serum concentrations,<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1093/humrep/deh888}}</ref> oxidative stress and inflammation in postmenopausal women with urinary concentrations,<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1016/j.envres.2009.04.014}}</ref> externalizing behaviors in two-year old children, especially among female children, with mother's urinary concentrations,<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1289/ehp.0900979}}</ref> altered hormone levels in men<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1021/es9028292}}</ref><ref>{{Cite pmid|20494855}}</ref> and declining male sexual function<ref>{{Cite journal |author=Li DK |title=Relationship between Urine Bisphenol-A (BPA) Level and Declining Male Sexual Function |journal=J Androl |volume= 31|issue= 5|pages= 500–6|year=2010 |month=May |pmid=20467048 |doi=10.2164/jandrol.110.010413 |url= |author-separator=, |author2=Zhou Z |author3=Miao M |display-authors=3 |last4=He |first4=Y. |last5=Qing |first5=D. |last6=Wu |first6=T. |last7=Wang |first7=J. |last8=Weng |first8=X. |last9=Ferber |first9=J. }}</ref> with urinary concentrations. |

|||

The Canadian Health Measures Survey, 2007 to 2009 published in 2010 found that teenagers carry 30 percent more l bisphenol A (BPA) in their bodies than older adults. The reason for this is not known.<ref>{{Cite news | title = Bisphenol A concentrations in the Canadian population, 2007 to 2009 | date = 16 August 2010 | url = http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-625-x/2010002/article/11327-eng.htm | work=Statistics Canada | pages = 82–625–XWE | accessdate = 19 November 2010}}</ref> A 2010 study that analyzed BPA urinary concentrations has concluded that for people under 18 years of age BPA may negatively impact human immune function.<ref>{{Cite pmid|21062687}}</ref> A study done in 2010 reported the daily excretion levels of BPA among European adults in a large-scale and high-quality population-based sample, and it was shown that higher BPA daily excretion was associated with an increase in serum total [[testosterone]] concentration in men.<ref>[http://ehp03.niehs.nih.gov/article/fetchArticle.action?articleURI=info%3Adoi%2F10.1289%2Fehp.1002367d ]{{dead link|date=October 2011}}</ref> A 2011 study found higher BPA levels in women with [[polycystic ovary syndrome]] compared to controls. Furthermore, researchers found a statistically significant positive association between male sex hormones and BPA in these women, suggesting a potential role of BPA in ovarian dysfunction.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/01/110113082720.htm |title=Bisphenol A may have role in ovarian dysfunction |doi=10.1210/jc.2010-1658 |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2011-01-13 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> A 2010 study found that people over age 18 with higher levels of BPA exposure had higher CMV [[antibody]] levels, which suggests their cell-mediated [[immune system]] may not be functioning properly.<ref>Antibacterial Soaps: Being Too Clean Can Make People Sick, Study Suggests: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/11/101129101920.htm</ref> |

|||

=====Sexual difficulties===== |

|||

A 2009 study on Chinese workers in BPA factories found that workers were four times more likely to report [[erectile dysfunction]], reduced sexual desire and overall dissatisfaction with their sex life than workers with no heightened BPA exposure.<ref>{{Cite journal |

|||

|author=D. Li, Z. Zhou, D. Qing, Y. He, T. Wu, M. Miao, J. Wang, X. Weng, J.R. Ferber, L.J. Herrinton, Q. Zhu, E. Gao, H. Checkoway, and W. Yuan |

|||

|title=Occupational exposure to bisphenol-A (BPA) and the risk of Self-Reported Male Sexual Dysfunction |

|||

|journal=Human Reproduction |

|||

|volume= 25|issue= 2|pages= 519–27|year=2009 |month= |

|||

|pmid= 19906654|pmc= |doi=10.1093/humrep/dep381 |

|||

|url=}}</ref> BPA workers were also seven times more likely to have ejaculation difficulties. They were also more likely to report reduced sexual function within one year of beginning employment at the factory, and the higher the exposure, the more likely they were to have sexual difficulties.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ajc.com/health/content/shared-auto/healthnews/envm/632954.html |title=BPA Tied to Impotence in Men |publisher=Ajc.com |date=2009-11-11 |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

====Historical studies==== |

|||

The first evidence of the [[estrogenicity]] of bisphenol A came from experiments on rats conducted in the 1930s,<ref>{{Cite journal | author=Dodds E. C., Lawson Wilfrid | year = 1936 | title = Synthetic Œstrogenic Agents without the Phenanthrene Nucleus | url = | journal=Nature | volume = 137 | issue =3476 | page = 996 |bibcode=1936Natur.137..996D | doi=10.1038/137996a0}}</ref><ref>E. C. Dodds and W. Lawson, ''Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences'', 125, #839 (27-IV-1938), pp. 222–232.</ref> but it was not until 1997 that adverse effects of low-dose exposure on laboratory animals were first reported.<ref name=C&ENews/> |

|||

===Low-dose exposure in animals=== |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Dose (µg/kg/day) |

|||

! Effects (measured in studies of mice or rats,<br />descriptions (in quotes) are from [[Environmental Working Group]])<ref name="globemittelstaedt">{{Cite news | last=Mittelstaedt | first=Martin | title='Inherently toxic' chemical faces its future | date=7 April 2007 | url=http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20070406.wbisphenolA0407/BNStory/National/ | accessdate=7 April 2007 | publisher=Globe & Mail | location=Toronto}}</ref><ref name="EWG-BPA">This table is adapted from: EWG, 2007. "Many studies confirm BPA's low-dose toxicity across a diverse range of toxic effects," Environmental Working Group Report: A Survey of Bisphenol A in U.S. Canned Foods. Accessed 4 November 2007 at http://www.ewg.org/node/20941. All studies included in this table where judged by the CEHRH panel to be at least of moderate usefulness for assessing the risk of BPA to human reproduction.</ref> |

|||

! Study Year |

|||

|- |

|||

| 0.025 |

|||

| "Permanent changes to genital tract" |

|||

| 2005<ref name="pmid15689538">{{Cite journal |author=Markey CM, Wadia PR, Rubin BS, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM |title=Long-term effects of fetal exposure to low doses of the xenoestrogen bisphenol-A in the female mouse genital tract |journal=[[Biol. Reprod.]] |volume=72 |issue=6 |pages=1344–51 |year=2005 |pmid=15689538 |doi=10.1095/biolreprod.104.036301 |url=http://www.biolreprod.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15689538}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 0.025 |

|||

| "Changes in breast tissue that predispose cells to hormones and carcinogens" |

|||

| 2005<ref name="pmid15919749">{{Cite journal |author=Muñoz-de-Toro M |title=Perinatal exposure to bisphenol-A alters peripubertal mammary gland development in mice |journal=[[Endocrinology (journal)|Endocrinology]] |volume=146 |issue=9 |pages=4138–47 |year=2005 |pmid=15919749 |doi=10.1210/en.2005-0340 |url=http://endo.endojournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15919749 |pmc=2834307 |author-separator=, |author2=Markey CM |author3=Wadia PR |display-authors=3 |last4=Luque |first4=EH |last5=Rubin |first5=BS |last6=Sonnenschein |first6=C |last7=Soto |first7=AM}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1 |

|||

| long-term adverse reproductive and carcinogenic effects |

|||

| 2009<ref name="pmid19590677"/> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 2 |

|||

| "increased prostate weight 30%" |

|||

| 1997<ref name="pmid9074884">{{Cite journal |author=Nagel SC, vom Saal FS, Thayer KA, Dhar MG, Boechler M, Welshons WV |title=Relative binding affinity-serum modified access (RBA-SMA) assay predicts the relative in vivo bioactivity of the xenoestrogens bisphenol A and octylphenol |journal=[[Environ. Health Perspect.]] |volume=105 |issue=1 |pages=70–6 |year=1997 |pmid=9074884 |doi=10.2307/3433065 |pmc=1469837 |jstor=3433065}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 2<!-- abstract says says 2.0, EWG report says 2.4 --> |

|||

| "lower bodyweight, increase of [[anogenital distance]] in both genders, signs of early puberty and longer estrus." |

|||

| 2002<ref name="pmid11955942">{{Cite journal |author=Honma S, Suzuki A, Buchanan DL, Katsu Y, Watanabe H, Iguchi T |title=Low dose effect of in utero exposure to bisphenol A and diethylstilbestrol on female mouse reproduction |journal=[[Reprod. Toxicol.]] |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=117–22 |year=2002 |pmid=11955942 |doi= 10.1016/S0890-6238(02)00006-0|url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0890623802000060}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 2.4 |

|||

| "Decline in testicular testosterone" |

|||

| 2004<ref name="pmid14605012">{{Cite journal |author=Akingbemi BT, Sottas CM, Koulova AI, Klinefelter GR, Hardy MP |title=Inhibition of testicular steroidogenesis by the xenoestrogen bisphenol A is associated with reduced pituitary luteinizing hormone secretion and decreased steroidogenic enzyme gene expression in rat Leydig cells |journal=[[Endocrinology (journal)|Endocrinology]] |volume=145 |issue=2 |pages=592–603 |year=2004 |pmid=14605012 |doi=10.1210/en.2003-1174 |url=http://endo.endojournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14605012}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 2.5 |

|||

| "Breast cells predisposed to cancer" |

|||

| 2007<ref name="pmid17123778">{{Cite journal |author=Murray TJ, Maffini MV, Ucci AA, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM |title=Induction of mammary gland ductal hyperplasias and carcinoma in situ following fetal bisphenol A exposure |journal=[[Reprod. Toxicol.]] |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=383–90 |year=2007 |pmid=17123778 |doi=10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.10.002 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0890-6238(06)00263-2 |pmc=1987322}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 10 |

|||

| "Prostate cells more sensitive to hormones and cancer" |

|||

| 2006<ref name="pmid16740699">{{Cite journal |author=Ho SM, Tang WY, Belmonte de Frausto J, Prins GS |title=Developmental exposure to estradiol and bisphenol A increases susceptibility to prostate carcinogenesis and epigenetically regulates phosphodiesterase type 4 variant 4 |journal=[[Cancer Res.]] |volume=66 |issue=11 |pages=5624–32 |year=2006 |pmid=16740699 |doi=10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0516 |url=http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16740699 |pmc=2276876}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 10 |

|||

| "Decreased maternal behaviors" |

|||

| 2002<ref name="pmid12060838">{{Cite journal |author=Palanza PL, Howdeshell KL, Parmigiani S, vom Saal FS |title=Exposure to a low dose of bisphenol A during fetal life or in adulthood alters maternal behavior in mice |journal=[[Environ. Health Perspect.]] |volume=110 Suppl 3 |issue= |pages=415–22 |year=2002 |pmid=12060838 |doi= |url=http://ehpnet1.niehs.nih.gov/docs/2002/suppl-3/415-422palanza/abstract.html |pmc=1241192}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

<!-- values in abstract (PMID 15079872) don't agree with LOAEL listed in EWG report| 30 |

|||

| "Hyperactivity" |

|||

| 2004 |

|||

|- --> |

|||

| 30 |

|||

| "Reversed the normal sex differences in brain structure and behavior" |

|||

| 2003<ref name="pmid12631470">{{Cite journal |author=Kubo K, Arai O, Omura M, Watanabe R, Ogata R, Aou S |title=Low dose effects of bisphenol A on sexual differentiation of the brain and behavior in rats |journal=[[Neurosci. Res.]] |volume=45 |issue=3 |pages=345–56 |year=2003 |pmid=12631470 |doi= 10.1016/S0168-0102(02)00251-1|url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168010202002511}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 50 |

|||

| Adverse neurological effects occur in [[primates|non-human primates]] |

|||

| 2008<ref name="pmid18768812" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| 50 |

|||

| Disrupts ovarian development |

|||

| 2009<ref name="pmid19535786"/> |

|||

|} |

|||

<!-- controversial |

|||

A study from 2008 concluded that blood levels of bisphenol A in neonatal mice are the same whether it is injected or ingested.<ref name="pmid18295446">{{Cite journal |author=Taylor JA, Welshons WV, Vom Saal FS |title=No effect of route of exposure (oral; subcutaneous injection) on plasma bisphenol A throughout 24h after administration in neonatal female mice |journal=Reprod. Toxicol. |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=169–76 |year=2008 |month=February |pmid=18295446 |doi=10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.01.001 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0890-6238(08)00002-6 |accessdate=5 May 2008}}</ref>--> |

|||

The current U.S. human exposure limit set by the EPA is 50 µg/kg/day.<ref>EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). 1988. [http://www.epa.gov/iris/subst/0356.htm Oral RfD Assessment: Bisphenol A. Integrated Risk Information System].</ref> |

|||

<!-- Ongoing discussion |

|||

In a 2010 commentary a group of scientists criticized a study designed to test low dose BPA exposure published in ''"Toxicological Sciences"''<ref>{{Cite pmid|19864446}}</ref> and a later editorial by the same journal,<ref>{{Cite pmid|20147444}}</ref> which claimed the rats used in the study were insensitive to estrogen and that had other problems like the use of polycabornate cages<ref name="Vom2010" /> while the authors disagreed.<ref>{{Cite pmid|20207694}}</ref> |

|||

--> |

|||

===Xenoestrogen=== |

|||

There is evidence that bisphenol A functions as a [[xenoestrogen]] by binding strongly to [[estrogen-related receptor gamma|estrogen-related receptor γ]] (ERR-γ).<ref name=matsushima/> This [[orphan receptor]] (endogenous ligand unknown) behaves as a constitutive activator of transcription. BPA seems to bind strongly to ERR-γ ([[dissociation constant]] = 5.5 nM), but not to the [[estrogen receptor]] (ER).<ref name=matsushima/> BPA binding to ERR-γ preserves its basal constitutive activity.<ref name=matsushima/> It can also protect it from deactivation from the [[selective estrogen receptor modulator]] [[4-hydroxytamoxifen]].<ref name="matsushima">{{Cite journal | author=Matsushima A, Kakuta Y, Teramoto T, Koshiba T, Liu X, Okada H, Tokunaga T, Kawabata S, Kimura M, Shimohigashi Y | title = Structural evidence for endocrine disruptor bisphenol A binding to human nuclear receptor ERR gamma | journal=J. Biochem. | volume = 142 | issue = 4 | pages = 517–24 | year = 2007 | month = October | pmid = 17761695 | doi = 10.1093/jb/mvm158 | url = }}</ref> |

|||

Different expression of ERR-γ in different parts of the body may account for variations in bisphenol A effects. For instance, ERR-γ has been found in high concentration in the [[placenta]], explaining reports of high bisphenol accumulation in this tissue.<ref name="pmid19304792">{{Cite journal | author=Takeda Y, Liu X, Sumiyoshi M, Matsushima A, Shimohigashi M, Shimohigashi Y | title = Placenta expressing the greatest quantity of bisphenol A receptor ERR{gamma} among the human reproductive tissues: Predominant expression of type-1 ERRgamma isoform | journal=J. Biochem. | volume = 146 | issue = 1 | pages = 113–22 | year = 2009 | month = July | pmid = 19304792 | doi = 10.1093/jb/mvp049 | url = }}</ref> |

|||

==Human exposure sources== |

|||

{{rquote|right|The problem is, BPA is also a synthetic estrogen, and plastics with BPA can break down, especially when they're washed, heated or stressed, allowing the chemical to leach into food and water and then enter the human body. That happens to nearly all of us; the CDC has found BPA in the urine of 93% of surveyed Americans over the age of 6. If you don't have BPA in your body, you're not living in the modern world. |[http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1976909_1976908_1976938-2,00.html The Perils of Plastic], [[TIME Magazine]]<ref name="timeBPA1">{{Cite news|url=http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1976909_1976908_1976938-2,00.html|title=The Perils of Plastic - Environmental Toxins - TIME|last=Walsh|first=Bryan|date=Thursday, 1 Apr. 2010|work=TIME|accessdate=2 July 2010}}</ref>}} |

|||

Bisphenol A has been known to be leached from the plastic lining of canned foods<ref>[http://www.ewg.org/reports/bisphenola Environmental Working Group]</ref> and polycarbonate [[plastics]], especially those cleaned with harsh detergents or that contain acidic or high-temperature liquids. BPA is an ingredient in the internal coating of metal food and beverage cans used to protect the food from direct contact with the can. A recent [[Health Canada]] study found that the majority of canned [[soft drink]]s it tested had low, but measurable levels of bisphenol A.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/securit/packag-emball/bpa/bpa_survey-enquete-can-eng.php|title=Survey of Bisphenol A in Canned Drink Products|last=Health Canada|accessdate=13 March 2009}}</ref> Furthermore, a study conducted by the University of Texas School of Public Health in 2010, found BPA in 63 of 105 samples of fresh and canned foods, foods sold in plastic packaging, and in cat and dog foods in cans and plastic packaging. This included fresh turkey, canned green beans, and canned infant formula.<ref>{{Cite pmid|21038926}}</ref> While most human exposure is through diet, exposure can also occur through air and through skin absorption.<ref name="Melzer et al.">{{Cite journal |author=Lang IA Galloway TS, Scarlett A, Henley WE, Depledge M, Wallace, Robert B, Melzer, D |title=Association of Urinary Bisphenol A Concentration With Medical Disorders and Laboratory Abnormalities in Adults |journal=[[Journal of the American Medical Association|JAMA]] |volume= 300|issue= 11|pages= 1303–10|year=2008 |pmid= 18799442|doi=10.1001/jama.300.11.1303 |url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/300.11.1303}}</ref> |

|||

A 2011 study published in ''Environmental Health Perspectives'', “Food Packaging and Bisphenol A and Bis(2-Ethyhexyl) Phthalate Exposure: Findings from a Dietary Intervention," selected 20 participants based on their self-reported use of canned and packaged foods to study BPA. Participants ate their usual diets, followed by three days of consuming foods that were not canned or packaged. The study's findings include: 1) evidence of BPA in participants’ urine decreased by 50% to 70% during the period of eating fresh foods; and 2), participants’ reports of their food practices suggested that consumption of canned foods and beverages and restaurant meals were the most likely sources of exposure to BPA in their usual diets. The researchers note that, even beyond these 20 participants, BPA exposure is widespread, with detectable levels in urine samples in more than an estimated 90% of the U.S. population.<ref>{{cite web|url = http://journalistsresource.org/studies/society/health/food-packaging-diet-bpa-chemical/ |title = Food Packaging and Bisphenol A and Bis(2-Ethyhexyl) Phthalate Exposure: Findings from a Dietary Intervention|publisher = Journalist's Resource.org }}</ref> |

|||

Free BPA is found in high concentration in [[thermal paper]] and [[carbonless copy paper]], which would be expected to be more available for exposure than BPA bound into resin or plastic.<ref name="ReferenceA"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/48084/title/Concerned_about_BPA_Check_your_receipts|title=Concerned About BPA: Check Your Receipts|last=Raloff|first=Janet|date=7 October 2009|publisher=Society for Science and the Public|accessdate=7 October 2009}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|url=http://rcswww.urz.tu-dresden.de/~gehring/deutsch/dt/vortr/040929ge.pdf|format=PDF|title=Bisphenol A Contamination of Wastepaper, Cellulose and Recycled Paper Products|last=Gehring|first=Martin| coauthors = Tennhardt, L., Vogel, D., Weltin, D., Bilitewski, B. | series = Waste Management and the Environment II. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, vol. 78 |year=2004|publisher=WIT Press|accessdate=15 October 2009|laysummary=http://rcswww.urz.tu-dresden.de/~gehring/deutsch/dt/poster/030331g2.pdf}}</ref> Popular uses of thermal paper include receipts, event and cinema tickets, labels, and airline tickets. A Swiss study found that 11 of 13 thermal printing papers contained {{nowrap|8 – 17 g/kg}} {{nowrap|Bisphenol A}} (BPA). Upon dry finger contact with a thermal paper receipt, roughly {{nowrap|1 μg}} BPA ({{nowrap|0.2 – 6 μg}}) was transferred to the forefinger and the middle finger. For wet or greasy fingers approximately {{nowrap|10 times}} more was transferred. Extraction of BPA from the fingers was possible up to {{nowrap|2 hours}} after exposure.<ref name="citeulike_receipt_7497437">[http://www.citeulike.org/article/7497437 Transfer of bisphenol A from thermal printer paper to the skin] 100821 citeulike.org</ref> While there is little concern for dermal absorption of BPA, free BPA can readily be transferred to skin, and residues on hands can be ingested.<ref name="epa-action-plan"/> |

|||

Studies conducted by the [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|CDC]] found bisphenol A in the urine of 95% of adults sampled in 1988–1994<ref name="pmid15811827">{{Cite journal |author=Calafat AM, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Caudill SP, Ekong J, Needham LL |title=Urinary concentrations of bisphenol A and 4-nonylphenol in a human reference population |journal=[[Environ. Health Perspect.]] |volume=113 |issue=4 |pages=391–5 |year=2005 |pmid=15811827 |doi= 10.1289/ehp.7534|url=http://ehpnet1.niehs.nih.gov/members/2004/7534/7534.html |pmc=1278476}}</ref> and in 93% of children and adults tested in 2003–04.<ref name="pmid18197297">{{Cite journal |author=Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Reidy JA, Needham LL |title=Exposure of the U.S. population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003–2004 |journal=[[Environ. Health Perspect.]] |volume=116 |issue=1 |pages=39–44 |year=2008 |pmid=18197297 |doi=10.1289/ehp.10753 |pmc=2199288}}</ref> While the EPA considers exposures up to 50 µg/kg/day to be safe, the most sensitive animal studies show effects at much lower doses.<ref name="globemittelstaedt"/><ref>[http://www.epa.gov/iris/subst/0356.htm Bisphenol A] – [[United States Environmental Protection Agency]]</ref> |

|||

In 2009, a study found that drinking from polycarbonate bottles increased urinary bisphenol A levels by two thirds, from 1.2 micrograms/gram creatinine to 2 micrograms/gram creatinine.<ref>{{Cite journal |author=Carwile JL, Luu HT, Bassett LS, Driscoll DA, Yuan C, Chang JY, Ye X, Calafat AM, Michels KB |title=Use of Polycarbonate Bottles and Urinary Bisphenol A Concentrations |journal=Environ. Health Perspect. |volume= 117|issue= 9|pages= 1368–72|year=2009 |month= |pmc= 2737011|doi=10.1289/ehp.0900604 |url=http://www.ehponline.org/members/2009/0900604/0900604.pdf |pmid=19750099}}</ref> Consumer groups recommend that people wishing to lower their exposure to bisphenol A avoid [[canned food]] and [[polycarbonate]] plastic containers (which shares [[resin identification code]] 7 with many other plastics) unless the packaging indicates the plastic is bisphenol A-free.<ref>[http://www.loe.org/shows/segments.htm?programID=08-P13-00038&segmentID=4 War of the Sciences] Air Date: Week of 19 September 2008 – Ashley Ahearn, Living on Earth</ref> To avoid the possibility of BPA leaching into food or drink, the National Toxicology Panel recommends avoiding microwaving food in plastic containers, putting plastics in the dishwasher, or using harsh detergents.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=94680753 |title=FDA Weighs Safety Of Bisphenol A |publisher=Npr.org |date= |accessdate=2011-10-23}}</ref> |

|||

In the U.S., consumption of soda, school lunches, and meals prepared outside the home was statistically significantly associated with higher urinary BPA.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1038/jes.2010.9}}</ref> This cannot be correlated with polycarbonate plastic,which is far too expensive to be used in packaging of such products, so it remains to be seen where this BPA is coming from. |

|||

BPA is also used to form epoxy resin coating of water pipes. In older buildings, such resin coatings are used to avoid replacement of deteriorating hot and cold water pipes.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aceduraflo.com/fixmypipes.html|title=Pipeline relining|accessdate=18 October 2010}}</ref> |

|||

===Fetal and early-childhood exposures=== |

|||

Children may be more susceptible to BPA exposure than adults. A recent study found higher urinary concentrations in young children than in adults under typical exposure scenarios.<ref>{{Cite pmid|19440506}}</ref> This increased susceptibility is most likely based on their reduced capacity to eliminate [[xenobiotics]]<ref>{{Cite pmid|18406467}}</ref> and also their estimated higher daily exposure to BPA, adjusted for weight, compared to adults.<ref>{{cite web | title = European Food Safety Authority Opinion | url =http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/science/afc/afc_opinions/bisphenol_a.html | format = Abstract | accessdate = 25 March 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Infants fed with liquid formula are among the most exposed, and those fed formula from polycarbonate bottles can consume up to 13 micrograms of bisphenol A per kg of body weight per day (μg/kg/day; see table below).<ref>{{cite web | title = European Food Safety Authority Opinion | url =http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/science/afc/afc_opinions/bisphenol_a.html | format = Abstract | accessdate = 28 February 2007}}</ref> In the US and Canada, BPA has been found in infant liquid formula in concentrations varying from 0.48 to 11 ng/g.<ref name="infantformulaUS">{{Cite pmid|20102208}}</ref><ref>{{Cite pmid|18702469}}</ref> BPA has been rarely found in infant powder formula (only 1 of 14).<ref name="infantformulaUS"/> While breast milk is the optimal source of nutrition for infants, it is not always an option. The [[U.S. Department of Health & Human Services]] (HHS) states that "the benefit of a stable source of good nutrition from infant formula and food outweighs the potential risk of BPA exposure.".<ref>{{cite web | title = Bisphenol A (BPA) Information for Parents | url=http://www.hhs.gov/safety/bpa/|publisher=[[U.S. Department of Health and Human Services]]|accessdate=25 March 2011}}</ref> |

|||

A 2010 study of people in Austria, Switzerland, and Germany has suggested polycarbonate (PC) baby bottles as the most prominent role of exposure for infants, and canned food for adults and teenagers.<ref>{{Cite doi|10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01345.x}}</ref> In the United States, the growing concern over BPA exposure in infants in recent years has led the manufacturers of plastic baby bottles to stop using BPA in their bottles. However, babies may still be exposed if they are fed with old or hand-me-down bottles bought before the companies stopped using BPA. |

|||

One often overlooked source of exposure occurs when a pregnant woman is exposed, thereby exposing the fetus. Animal studies have shown that BPA can be found in both the placenta and the amniotic fluid of pregnant mice.<ref>{{Cite PMID|12611660}}</ref> A small US study in 2009, funded by the [[Environmental Working Group|EWG]], detected an average of 2.8 ng/mL BPA in the blood of 9 out of the 10 [[umbilical cord]]s tested.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ewg.org/files/2009-Minority-Cord-Blood-Report.pdf|title=Cord Blood Contaminants in Minority Newborns|year=2009|publisher=[[Environmental Working Group]]|accessdate=2 December 2009}}</ref> A study of 244 mothers indicated that exposure to BPA before birth could affect the behavior of girls' at age 3. Girls whose mother's urine contained high levels of BPA during pregnancy scored worse on tests of anxiety and hyperactivity. Although these girls still scored within a normal range, for every 10-fold increase in the BPA of the mother, the girls scored at least six points lower on the tests. Boys did not seem to be affected by their mother's BPA levels during pregnancy.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.statesman.com/news/nation/study-links-bpa-with-girls-behavior-problems-1930237.html?cxtype=rss_news|title=Study links BPA with girls' behavior problems|year=2011|publisher=[[Austin American Statesman]]|accessdate=24 October 2011}}</ref> After the baby is born, maternal exposure can continue to affect the infant through transfer of BPA to the infant via breast milk.<ref>{{Cite PMID|15386523}}</ref><ref>{{Cite PMID|16377264}}</ref> Because of these exposures that can occur both during and after pregnancy, mothers wishing to limit their child’s exposure to BPA should attempt to limit their own exposures during that time period. |

|||

While the majority of exposures have been shown to come through the diet, accidental ingestion can also be considered a source of exposure. One study conducted in Japan tested plastic baby books to look for possible leaching into saliva when babies chew on them.<ref>{{Cite PMID|20508389}}</ref> While the results of this study have yet to be replicated, it gives reason to question whether exposure can also occur in infants through ingestion by chewing on certain books or toys. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Population |

|||

! Estimated daily bisphenol A intake, μg/kg/day.<br />Table adapted from the National Toxicology Program Expert Panel Report. |

|||

|- |

|||

| Infant (0–6 months)<br />formula-fed |

|||

| <center>1–24</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| Infant (0–6 months)<br />breast-fed |

|||

| <center>0.2–1 </center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| Infant (6–12 months) |

|||

| <center>1.65–13</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| Child (1.5–6 years) |

|||

| <center>0.043–14.7</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| Adult |

|||

| <center>0.008–1.5</center> |

|||

|} |

|||

==Pharmacokinetics== |

|||

There is no agreement between scientists of a [[Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modelling|physiologically-based]] [[pharmacokinetic]] (PBPK) BPA model for humans. The effects of BPA on an organism depend on how much free BPA is available and for how long cells are exposed to it. [[Glucuronidation]] in the liver, by conjugation with glucuronic acid to form the metabolite BPA-glucuronide (BPAG),<ref name="epa-action-plan"/> reduces the amount of free BPA, however BPAG can be deconjugated by [[beta-glucuronidase]], an enzyme present in high concentration in placenta and other tissues.<ref name="Ginsberg"/><ref name="placenta">{{Cite pmid|20382578}}</ref> Free BPA can also be inactivated by sulfation, a process that can also be reverted by [[arylsulfatase C]].<ref name="Ginsberg">{{Cite journal|last=Gary Ginsberg and Deborah C. Rice|date=November 2009|title=Does Rapid Metabolism Ensure Negligible Risk from Bisphenol A?|journal=Environmental Health Perspectives|volume=117|issue=11|pages=1639–1643|url=http://www.ehponline.org/members/2009/0901010/0901010.pdf|accessdate=16 November 2009|pmid=20049111|first1=G|last2=Rice|first2=DC|doi=10.1289/ehp.0901010|pmc=2801165}}</ref> |

|||

A 2009 research study found that some drugs, like [[naproxen]], [[salicylic acid]], [[carbamazepine]] and [[mefenamic acid]] can, ''in vitro'', significantly inhibit BPA glucuronidation.<ref>{{Cite pmid|19916736}}</ref> A 2010 study on rats embryos has found that [[genistein]] may enhance developmental toxicity of BPA,<ref>{{Cite pmid|20299547}}</ref> and another 2010 vitro study has shown that placenta [[P-glycoprotein]] may efflux BPA from placenta.<ref>{{Cite pmid|20214975}}</ref> |

|||